WHITE RIVER TERRITORY

Since the beginning of civilized travel, the White River and its tributaries have been an obstacle to land transportation and commerce between Little Rock and Brinkley. The terrain is relatively flat in this region of the Grand Prairie, and floods along the White River routinely inundate a large area east of DeValls Bluff. Over time, efforts have been made to overcome the problems of high water, but the closure of Interstate 40 in May 2011 once again demonstrated the difficulty of taming the river. From Brinkley westward toward Little Rock, both the Rock Island and U.S. Highway 70 crossed first the Cache River (a tributary of the White River), and then the White River. Like the farmlands and roadways near the river, the railroad and the U.S. highway were both susceptible to flooding whenever the White River went on a rampage.

The White River bridge at DeValls Bluff was the Rock Island’s largest bridge between North Little Rock and West Memphis, and a source of frequent problems. The White River at DeValls Bluff has a swift current even at low water, and the fluctuations between high water and low water levels can be quite pronounced. Before upstream flood control projects partially tamed the river, the high water of late winter and early spring would often last until early July.1 This scenario was further complicated by federal regulations governing the bridging of navigable waterways; the original White River bridge (completed in April 1871 by the Memphis & Little Rock Railroad) included a center pier with a swing span to accommodate steamboat traffic.

In the latter part of 1920, pier 4 on the White River bridge was found to be leaning to the east, and the eccentric loading of the span between pier 4 and pier 5 had caused cracks to appear in pier 5. The top of this pier was bound with steel cable for reinforcement, and false work was driven to relieve the piers of some of their load. This repair was unsuccessful and pier 4 continued tipping, drifting some 15 inches out of alignment. High water delayed the start of repair efforts until December 1921; subsequent high water and fast current conditions further delayed completion of new piers 4 and 5 until January 1923. Some difficulty was encountered in removing the old 1870 piers, the stone having been set in a lime mortar which was exceptionally hard and tenacious - fully as strong as a Portland cement mortar. On February 26, 1923, a steamboat ran into and damaged pier #3, and the Rock Island decided that replacement of the entire bridge would be preferable to continued repair of the 1870s support structure.

Design of a new railroad bridge over the White River was started in 1923, with the American Bridge Company and the Kansas City Bridge Company handling various parts of the construction effort. Including the approaches, the new bridge was 2,671 feet long, with a 187-foot center span which was lifted vertically 55 feet to provide clearance for boats. Since the White River at the bridge site was 60 feet deep, sufficient vertical clearance was necessary for large boats. The new bridge, completed at a cost of over $800,000, was dedicated and placed in service on January 15, 1927.2 At about the same time that a new railroad bridge was being planned, a group of investors were securing permission to build a highway toll bridge to replace an existing ferry crossing of the White River at DeValls Bluff. Harry E. Bovay, of Stuttgart, chartered the White River Bridge Company and contracted with the Missouri Valley Bridge & Iron Company of Leavenworth, KS, to construct the bridge. The highway bridge was also a through truss with vertical lift span, quite similar to the new bridge being planned by Rock Island. The highway bridge had 80-foot towers which could raise the 204 foot center section over 50 feet above the river. The highway bridge was completed first and placed in service on January 1, 1925. The original toll was 5 cents per person or head of livestock, 75 cents for a car, and $1.00 for a six-horse carriage. The bridge was less than successful financially, and tolls were soon raised to $1.00 per car.

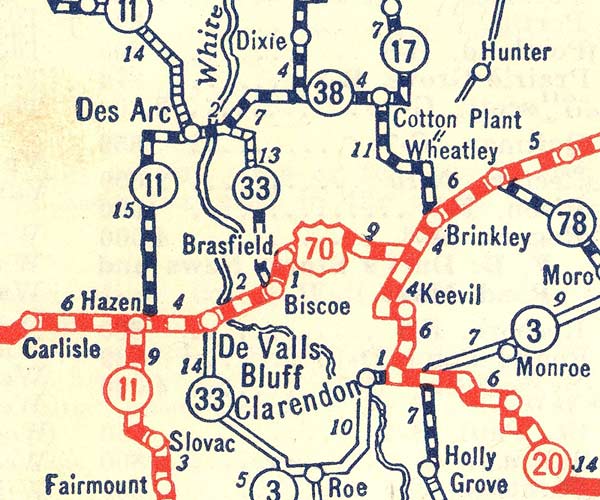

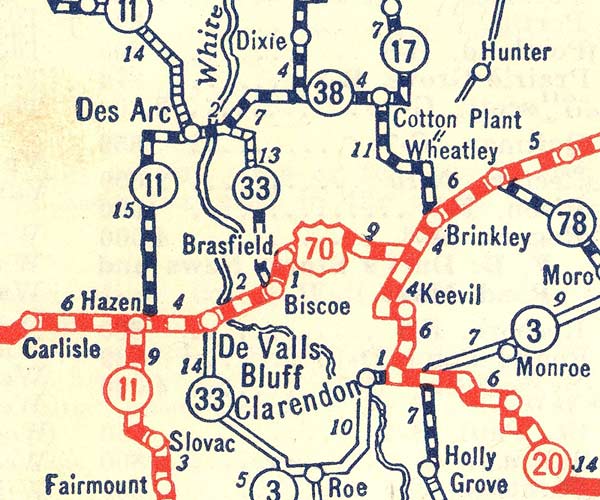

ARKANSAS HIGHWAYS IN 1928

On this 1928 map, U.S. Highway 70 through Brinkley was shown as "all-weather" graded gravel but not yet paved. When U.S. 70 was closed because of high water east of DeValls Bluff, the usual detour was a circuitous route via Cotton Plant and Des Arc which utilized state highways 38 and 11. A less desirable detour was possible via Clarendon, but this involved a ferry crossing of the White River during flood stage, as well as traversing unimproved roads from Clarendon back to U.S. 70 at DeValls Bluff.

PLANNING AND OPENING THE “BROADWAY OF AMERICA”

In 1928, with the nation in the midst of an unparalleled highway construction frenzy, the concept of the "Broadway of America" was born. Broadway of America was to be a paved concrete highway extending from Broadway in New York City to Broadway in San Diego. The route extended through Washington, D.C., Roanoke, Knoxville, Nashville, Memphis, Little Rock, Texarkana, Dallas, Fort Worth, Abilene, El Paso, Douglas, Tucson, Phoenix and Yuma. Between Memphis and Little Rock, the highway generally paralleled the Rock Island's main line, passing through Forrest City, Brinkley, and DeValls Bluff. West of DeValls Bluff, the highway was directly adjacent to the Rock Island for most of the remaining distance into Little Rock. All of the cities along the Broadway of America route expected to benefit from the increased automobile traffic, but the influx of tourist dollars had a disproportionately large impact on the economy of smaller towns.3

To officially open the route, publicity caravans originated on the east and west coasts en route to Memphis, where a celebration was scheduled near the Mississippi River bridge. In mid-April 1928, the west coast caravan (with various local additions along the way) motored from Little Rock to DeValls Bluff for a large fish fry sponsored by the DeValls Bluff Chamber of Commerce. High water between DeValls Bluff and Brinkley forced a circuitous detour via Cotton Plant, over unpaved roads that were barely passable because of the wet conditions. Brinkley's weekly newspaper, the Brinkley Argus, reported on April 26, 1928 that flood waters were 28 inches over the main highway along a five mile segment between Dagmar and Brasfield. The paper awarded a "Mud Medal" to Arkansas Highway Commission Chairman Dwight H. Blackwood, who was blamed for the failure to properly rebuild this segment of the route.

As was usually the case, the high water was only a minor nuisance to the Rock Island, and mainline train operations continued without significant delay. On the Newport branch, however, water was over the tracks four miles south of Newport. A boat was used to ferry mail, express, and passengers across the high water and into Newport, thus preserving some semblance of Rock Island service to that point during the 15 days that the tracks were flooded. High water also interrupted branch line train service between Mesa and Searcy during the same period. After a month, waters receded over flooded highway five miles west of Brinkley, thus allowing the Broadway of America to reopen on May 16, 1928. Unfortunately for motorists, the route was again jeopardized by high water in mid June, and the prospect of a levee failure near Georgetown on the White River threatened even more flooding. The Brinkley Argus on June 14 reported that water had crested at five feet above the highway during the previous flood, and might be expected to reach a depth of seven feet this time from the Chaney farm to Biscoe. The newspaper mentioned the possibility of a shuttle train to accommodate the tourist traffic which was rapidly dwindling as word of the flood spread. After water inundated the detour route via Cotton Plant, the few hardy motorists determined to make the trip were routed from Brinkley to Clarendon. The roads northwest from Clarendon were also flooded, so cars were carried upriver by ferry from Clarendon to DeValls Bluff. The straight line distance between DeValls Bluf and Clarendon is less than 11 miles, but the twists and bends of the river passage easily added another 5 miles of travel. Because of the time consumed by this detour, most long-distance tourists simply rerouted their trip to bypass central Arkansas altogether.

A front page feature in the June 28, 1928 issue of the Brinkley Argus was headlined WATER KILLS TOURIST CROP.

The high water and floods have played havoc with the great caravan of tourists that are accustomed to traveling through Brinkley en route to the east and west. When tourists are in full flight, Brinkley averages about 1,000 strangers in and out of town per day, and these people leave an average of $1,000 per day in Brinkley cash registers. There has been talk of a shuttle train on the Rock Island to DeValls Bluff, but Arkansas Division Superintendent J.A. McDougal and his force of 200 are preoccupied with saving their railroad from going out, and they naturally have not considered a shuttle train in this precarious condition. It is safe to predict that there will be a shuttle train from Brinkley to DeValls Bluff just as soon as the period of watchful waiting is over. In the meantime, Brinkley's tourist crop, like our drowned cotton, is not very promising.

Rock Island 4-6-0 No. 1429 is moving the shuttle train through flooded territory west of Brinkley in the summer of 1928. Floodwaters have engulfed the base of the telegraph pole line to the right. Of greater concern, the water also made the subgrade more unstable, necessitating slow operating speeds. Note that the locomotive was displaying white flags; all shuttle trains operated as extras. [Rock Island photo; Rock Island Magazine, August 1928.]

ROCK ISLAND SHUTTLE TRAIN SAVES TOURIST BUSINESS

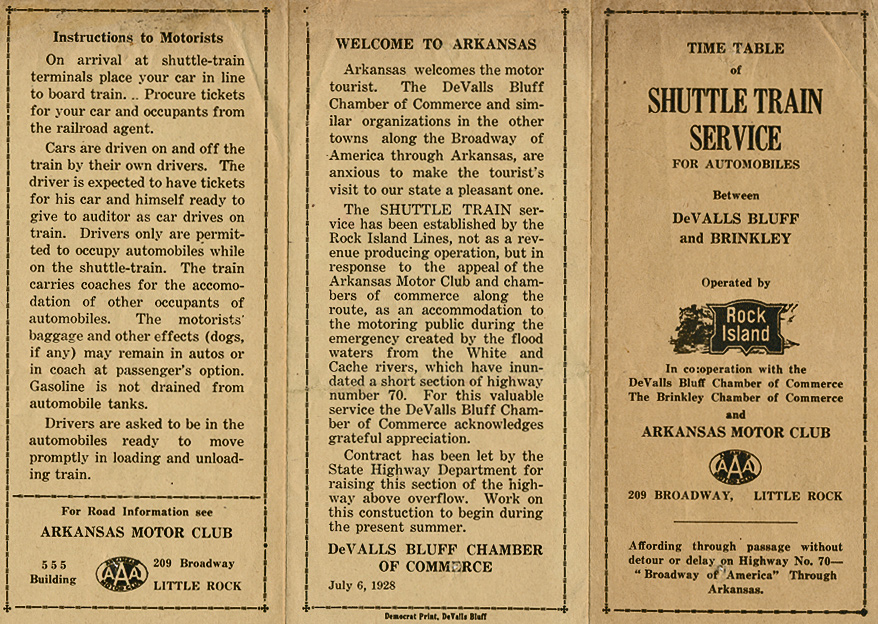

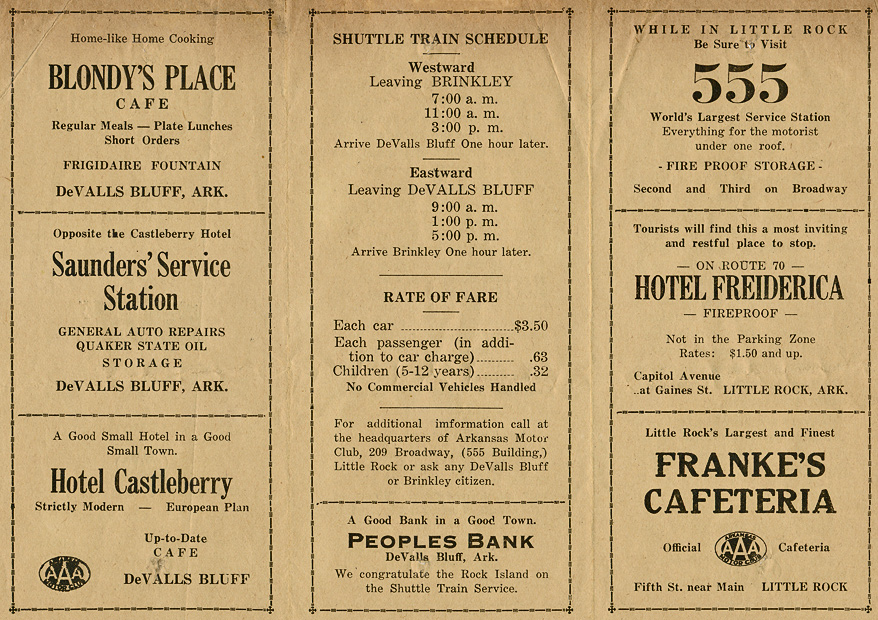

A shuttle train service to ferry automobiles across the flooded area was proposed following a conference between Rock Island officials and representatives of the Brinkley and DeValls Bluff Chambers of Commerce. Support was also voiced by representatives of the commercial bodies in Forrest City, Hazen, Little Rock, Hot Springs, and Memphis. Members of the Arkansas Highway Commission and the Arkansas Motor Club (AAA) also participated. Implementation of the service was delayed until it was certain that the railroad's main line would remain open. Rock Island maintenance crews worked constantly to keep the mainline open between Brinkley and Brasfield. This was the segment most threatened, with high water cresting only 3˝ feet below track level due to breaks in both the White River and Cache River levees. [This close call prompted the Rock Island to budget $146,000 for raising the tracks even higher through the flooded area, the largest single improvement in the railroad's annual flood control program.] Once the integrity of the main line was assured, the Rock Island assembled a shuttle train consisting of steel flatcars and several passenger coaches. Ten flatcars were initially modified with side guards and steel aprons connecting the cars, but additional cars were pressed into service on the first run, and a total of eighteen cars were ultimately modified for the "circus" style loading used with the shuttle service. A makeshift ticket office was opened in J.W. Hale's store on Cypress Street in Brinkley, and each automobile was charged $3.50 along with 63˘ for each adult passenger and half fare(32˘) for children 5-12. After driving their own automobile up the ramp and onto the flatcars, the drivers had the option of remaining with their auto or riding in one of two coaches provided. All other passengers from each auto were required to travel in the coaches. Each flatcar could accommodate three automobiles.

The first run of the shuttle train was made at 7 A.M. on Tuesday July 3, 1928, departing Brinkley with 37 automobiles and 92 passengers. After making its way across the flooded area, with high water of the White River surrounding the right of way for much of the distance, the train's cargo was unloaded just west of DeValls Bluff. This west side shuttle terminal was located where the railroad and highway were nearly adjacent and at the same grade level. Rock Island undoubtedly made provision for a ticket office here, to collect fares for eastbound passage. Three daily round trips were established with westbound departures from Brinkley at 7:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., and 3:00 p.m., and eastbound departures from DeValls Bluff at 9:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 5:00 p.m. This schedule allowed the shuttle to operate without affecting regularly scheduled freight and passenger trains. The Brinkley newspaper nicknamed the shuttle train The McDougal Limited, in appreciation for the superintendent's support of the emergency service.

Superintendent McDougal reported that 160 automobiles and 451 passengers were carried during the first day's operation, resulting in gross revenue to the railroad of $844.13. While this might seem to be a tidy profit for a day's work, the railroad actually incurred a sizable expense in orchestrating the shuttle runs. In addition to the cost of modifying the flat cars and providing an extra locomotive, train crew, and two coaches, the railroad also sent numerous officials to Brinkley to see that the first shuttle trips were operated smoothly. This group included Superintendent McDougal, trainmaster J.H. Dimmitt, traveling engineer O.J. Patterson, special agent J. Collins, traveling passenger agent Charles Roher, assistant general passenger agent H.H. Hunt, and auditors Mr. Dunlop and Mr. Hart. On the second day of the shuttle operation, a solicitor for the Clarendon ferry service appeared in Brinkley to try and divert business from the railroad at a cut rate price of $3.00 per carload (including passengers). Although passengers waiting to board the shuttle train at Brinkley were made aware of the less expensive ferry option, only a few drivers were willing to take the time required for the longer detour via Clarendon.

The shuttle service had become something of a spectacle itself by mid-July, with residents frequently pausing at the Brinkley plaza to marvel at the passing tourists. Automobiles waiting to board the shuttle ran the gamut from big Lincolns and Packards to Fords, Chevrolets, Pierce-Arrows, Whippets, Studebakers, and "...every kind of patched up contrivance bearing licenses from every state in the union as well as Canada, Mexico, Cuba, and Puerto Rico." On Wednesday July 11, 251 cars and 708 passengers were carried, producing gross revenues of $1,324 for the Rock Island. The Brinkley Argus reported that 273 cars and 808 passengers were carried on Sunday July 15, possibly the peak day of the shuttle operation.4 Flood waters slowly receded, and by July 24 the shuttle train was discontinued and regular highway travel was restored. At the time the special train service ended, it was expected that new construction along the low lying areas of Highway 70 would eliminate the threat of flooding by the time of the next high water season.

The Rock Island Magazine editorialized in August 1928 that:

Since the railroads perform their function so smoothly, they are usually taken for granted. It usually takes some emergency to awaken the public to the real value of the railroads. The Rock Island has come to the rescue again this year, with the unique shuttle service provided in Arkansas. Traffic representatives of the Rock Island, who were on the ground a great deal of the time while this shuttle train was operated, said they saw automobiles bearing licenses of practically every state in the Union. This steady stream of motorists and their cars were transported over 18 miles of flooded territory and went their way rejoicing over the service rendered by the Rock Island. No doubt, this unusual service will stick in their memories for a long time to come, and will serve to awaken them to a greater appreciation of the real value of the railroads.

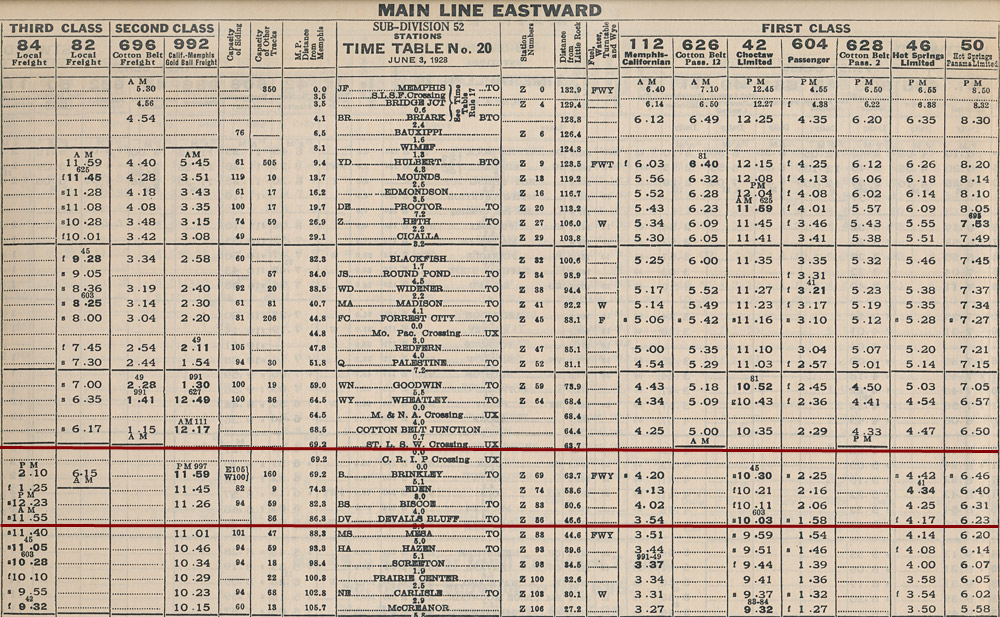

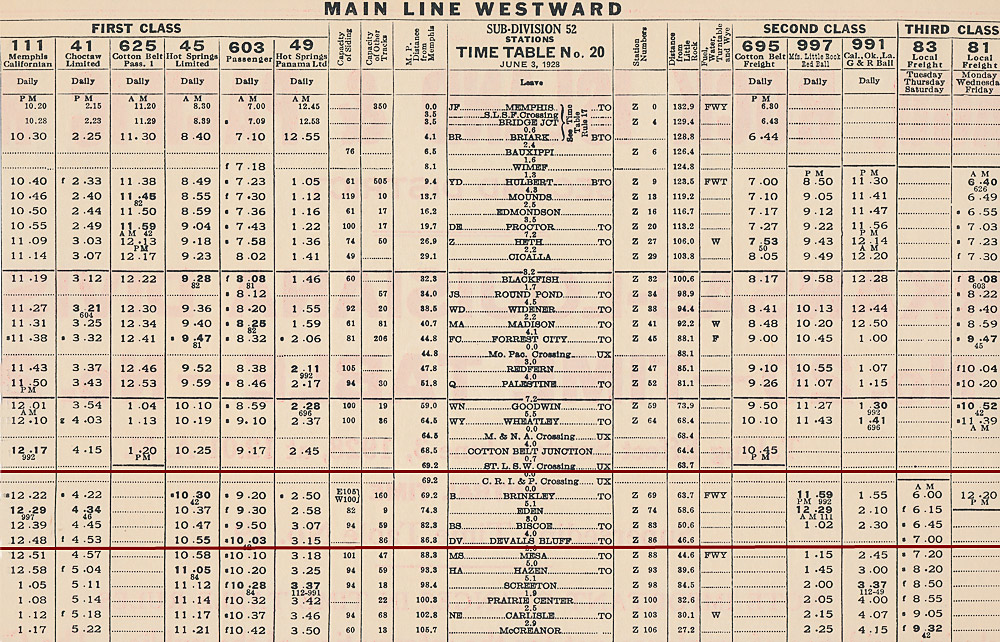

ARKANSAS-LOUISIANA DIVISION TIMETABLE No. 20, JUNE 3, 1928

RI SHUTTLE TRAIN RETURNS IN 1930

Despite highway improvements, the shuttle train returned during January 1930 when the Memphis-Little Rock highway was again inundated. Superintendent J.A. McDougal personally supervised the operation of the train, despite the discomforts of the bitterly cold weather at that time. During the initial days of operation, the ground was covered with snow. Traveling passenger agent Chas. H. Rohrer also spent much of January in Brinkley, looking after the business of the shuttle train. It is unknown whether a timetable was issued for the January 1930 shuttle operation.

A "real photo" postcard view of the shuttle train loading in the Brinkley yards on a cold and snowy January 24, 1930, with locomotive 1736 providing the power. The snow on the ground suggests a cold ride for any driver choosing to remain in their automobile. Presumably the passenger coaches were equipped with coal-burning stoves since the flatcars lacked steam lines.

On 30 January 1930, the Brinkley Argus reported that only a week or so of good weather would be required to complete a one-half mile section of Road #38 near Des Arc. Afterwards, through traffic was routed from Brinkley via Cotton Plant and Des Arc to Hazen, thus avoiding the flooded areas of the Cache and White River bottoms. The completion of this segment again eliminated the need for the Rock Island's shuttle train service, and the automobile conscious public soon forgot the railroad's contribution to keeping its competitor, the government subsidized highway, open.

HIGHWAY POLITICS AND THE SHUTTLE TRAIN

In addition to providing basic transportation, the shuttle train operation siphoned traffic from the privately owned toll bridge over the White River at DeValls Bluff. Almost from the time this highway bridge opened, toll charges had been a source of political friction. The $1.00 per car toll was viewed as excessive, and this dissatisfaction was constantly fueled by the adamantly anti-toll road philosophy advanced by Highway Commissioner Blackwood.5 Independent of the shuttle train operation, the Arkansas Highway Commission had requested a review of the toll by the War Department, which held jurisdiction in that matter. The bridge company had subsequently been ordered to reduce the maximum toll to 75˘, but the Highway Commission was still not satisfied. The fact that the railroad shuttle service brought economic pressure on the bridge company was seen as a collateral benefit pushing toward eventual state ownership of the bridge.6

To eliminate the complaints of high tolls from the White River bridge, the Arkansas Highway Commission made an offer to purchase the bridge from its owners. When this offer was rejected, condemnation proceedings were instituted in February 1930, and the structure was eventually acquired by the state. Tolls were immediately reduced from 75˘ to 50˘, with a promise of total elimination of the toll as soon as the purchase price of the bridge had been collected.7 It is perhaps merely coincidental that no railroad shuttle service was operated after this bridge was brought under the financial control of the Arkansas Highway Commission. Heavy rainfall during the first week of May 1930 again submerged Highway 70 at the Brasfield cut-off, but traffic was successfully detoured over the alternate route via Des Arc and Cotton Plant.8 All of the contracts for bridges necessary to finish the new Highway 70 were awarded by mid-summer 1930, placing the highway above all but the most extreme flood conditions, and eliminating the need for further railroad shuttle service.

POSTSCRIPT

Although the Rock Island was not called upon to provide further shuttle train service, the two White River lift bridges served as landmarks for their respective transportation modes for another 50 years. The last Rock Island train crossed the White River bridge early in the morning of March 24, 1980, as the last #39 operated from Memphis to Little Rock. [For details of this last train, see Rock Island Technical Society Digest No. 5, pages 59-62.] Cotton Belt briefly assumed control of this segment of the Rock Island but no through train operations were contemplated. To accommodate river navigation, the bridge was raised and locked in open position, and it that position it has remained, outlasting the railroad and even the tracks themselves, sitting derelict for the 3 decades and counting since the Rock Island’s demise. The unlikely survival of the bridge offers some remote hope that the Sunbelt route might one day be revived if this country ever achieves a rational national transportation policy.

The Highway 70 lift bridge, a few hundred yards downstream from the Rock Island bridge, continued in service, occasionally being closed for months at a time when one of the piers were struck by a barge trying to negotiate the treacherous currents. On April 9, 1990, the highway lift bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places, in recognition of being the oldest and last vertical-lift span used for highway traffic in Arkansas. In 2001, construction began on a new replacement bridge, the approaches using part of the now vacant Rock Island right of way. When preservation efforts failed, the Highway 70 lift bridge was blown up on July 20, 2004, several months after a new, higher bridge was opened for service. As part of this project, the Rock Island bridge was also supposed to be demolished after being deemed a navigation hazard. As of 2013, however, the center spans and lift section of the railroad bridge still stand, stripped of track, a rusting hulk but still a landmark in its own right. It is perhaps poetic justice that, during the high water of 2011, trucks diverted from flooded Interstate-40 were forced to navigate a many-mile detour rather than consider the possibility of a rail shuttle.

END NOTES: