Trolley Bus Operation in Little Rock, Arkansas

by Bill Pollard

Trolley coaches, electric transit vehicles on rubber tires rather than on rail, were a part of the Little Rock street scene for less than a decade... December 25, 1947 until March 1, 1955. While other cities embraced this form of mass transit for many years, Little Rock's transit operators, for a variety of reasons, succumbed to the allure of the diesel powered bus. This is a summary of the events which brough about the arrival and premature departure of these unique vehicles.

Transit ridership nationwide and in Little Rock was experiencing a gradual decline in the period between the Great Depression and World War II as more people became automobile owners. This decline was temporarily reversed during World War II due to rationing of both gasoline and rubber for tires. All Little Rock and North Little Rock transit operations had been consolidated as of January 31, 1935 as the Capital Transportation Company, a subsidiary of Arkansas Power & Light. Capital Transportation began a program of modernization, which in most cases meant replacement of streetcar lines with diesel buses. The rationing of World War II stopped coversion of the remaining Little Rock trolley lines and in fact resulted in the restoration of many stored trolley cars to service to handle heavy traffic demand. At the end of World War II, three streetcar lines remained in service:

- Pulaski Heights - the most heavily traveled line, extending from westward from downtown along Markham, then Kavanaugh to Hays Street (the present day North University)

- Fair Park - East 9th Street - two lines that were operated together, meaning that when a Fair Park car came off that line, it continued to the end of the East 9th line and then back again. This line served the baseball park in addition to Fair Park, and was also very heavily traveled at times.

- Highland - East 14th line - also two lines which were operated together. Traffic on these lines was not as heavy as the other two, but streets in the Highland area were not deemed adequate for bus operation.

Utility companies such as AP&L were gradually withdrawing from transit operations, partially because other business operations were more profitable and partly as a result of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 which encouraged utilities to sell assets that appeared to violate antitrust laws. World War II slowed that divestiture, but on July 5, 1946, the Arkansas Public Service Commission approved the sale of Little Rock and North Little Rock transit operations to Capital Transportation Company. This transaction placed central Arkansas transit operations more at arms length from AP&L's core utility operations, although some corporate relationship remained between the two companies. Capital Transportation Company planned to aggressively modernize operations by retiring all remaining streetcar operations, replacing 49 trolley cars with 29 electric trolley buses to be purchased at a cost of $460,000. A number of new diesel buses would also be purchased to allow retirement of some of the oldest existing buses. The conversion to trolley bus would require installation of 24 miles of wires for the new equipment, as well as paving the areas now occupied by trolley tracks.

The proposal for electric trolley coaches was not without some controversy. Alderman Roy Kumpe on August 8, 1946 introduced a resolution asking for the city council to study the trolley bus plan, calling the trolley buses an obsolete concept that was "...25 years behind the times." He cited "experts" from other cities that recommended diesel buses instead of electric buses, a bias later identified as largely funded by General Motors and their desire to eliminate electric transit systems and sell more buses. The alderman argued that "The trend in modern city planning is to get all wires underground - out of the way of the driving and walking public. They present a traffic hazard, and are dangerous to the lives of pedestrians." Never mind that the wires were far above the heads of pedestrians, and of course discounting the considerable exhaust and noise pollution generated by gasoline or diesel buses versus the clean virtually silent operation of electric buses. The resolution didn't pass, and planning for trolley bus operation continued.

The conversion of segments of Capital Transportation's streetcar system to trolley bus began with the discontinuance of streetcar service on the Pulaski Heights line, the most heavily utilized streetcar line in the city. The last streetcars on this line operated on August 31, 1947, with replacement service temporarily provided by 25 buses beginning the following day. At this time, the Pulaski Heights line began operating through with the South Main line, which had been converted from streetcar to bus some years earlier. At the same time, line crews began modifying the overhead wire to accommodate trolley bus operation. Electric streetcars required only a single overhead wire to supply electrical current, with the rails completing the circuit. Trolley buses had two parallel trolley poles, thus requiring a dual catenary system overhead which was considerably more complex, although it utilized many of the existing utility poles along the route. Dark green metal poles, rather than treated wood poles, were placed in some areas where the wire pull was greatest, and many of those poles survived for years after their original usage had ended. There had been some controversies over renewing the Capital Transportation franchise, but that was also resolved in August 1947, and a new 7-cent fare for both bus and streetcar riders was placed into effect on September 1. The initial plans for modernization of the system included eventual abandonment of the ancient carbarn at 1000 North Street. A new car barn was constructed for trolley buses, but the old trolley carbarn continued in service as a bus shop into the mid-1950s.

On December 25, 1947, streetcar service ended in Little Rock. The last two lines were the Fair Park line and the South Highland - East 14th Street line. On the following day, the first trolley coaches began revenue operation on the combined Pulaski Heights-South Main line, and gasoline powered buses moved from this line to the just discontinued streetcar routes. The new trolley bus line utilized 29 new trolley coaches (numbers 600-628) model TC-44, manufactured by American Car & Foundry-Brill at their Springfield, Massachusetts plant and delivered to Little Rock by rail. The trolley buses had seating for 44 passengers, and could operate at a maximum speed of 45mph. The trolley buses were delivered in an attractive postwar color scheme of red and cream with silver striping, replacing the green and white colors of earlier years. On Main Street, safety zones had been marked where passengers would cross the outer traffic lane to access street car tracks in the center of the street. The trackless trolleys could steer out from under their wires slightly, in order to load and discharge passengers at the curb, thus allowing automobile traffic to move unimpeded in the center lanes formerly occupied by streetcars.

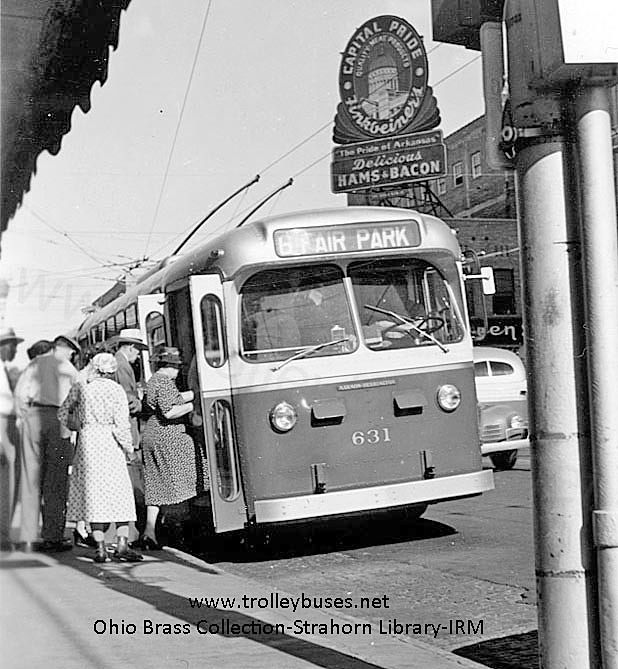

In early 1948 one of the new trolley buses can be seen loading passengers on the corner of 6th & Main. The photographer was standing on the northwest orner, looking toward the southeast, with Pfiefers Home Center and Standard Furniture Company in the background. The trolley bus was a route No. 8 - Pulaski Heights bus. Note the now unused streetcar tracks still visible, not yet paved over or removed. Photo by John Mills.

In early 1948 one of the new trolley buses can be seen loading passengers on the corner of 6th & Main. The photographer was standing on the northwest orner, looking toward the southeast, with Pfiefers Home Center and Standard Furniture Company in the background. The trolley bus was a route No. 8 - Pulaski Heights bus. Note the now unused streetcar tracks still visible, not yet paved over or removed. Photo by John Mills.

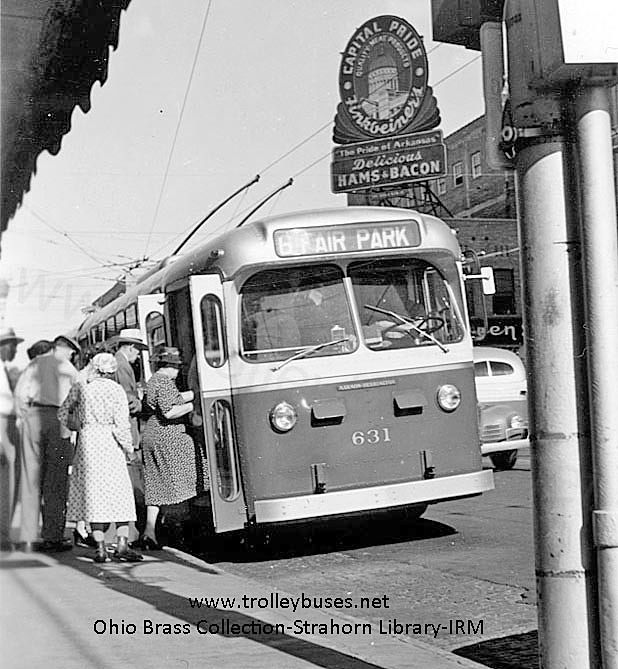

The trolley bus operation was deemed a success on the Pulaksi Heights line, and planning continued to convert the Fair Park route in 1948. This expansion necessitated the purchase of six additional trolley coaches (numbers 629-634), model TC-48 built by Marmon Herrington. In addition to catenary reconstruction similar to what had been required on the Pulaski Heights line, conversion of the Fair Park line also required paving the private right of way at the end of the line, near the baseball park. The Fair Park line bus replacement followed a temporary route pending the paving of the regular route. Buses followed the former route to 12th and Lewis, then west on 12th to East Jonesboro Drive (entrance to Fair Park), then north on East Jonesboro to 7th Street (in Fair Park), then return over the same route to Capitol Avenue and Cumberland, south on Cumberland to East 6th, west on 6th to Scott, north on Scott to East Capitol, and west on Capitol over regular route. On December 25, 1948, trolley buses replaced regular buses on the Fair Park line and also on the West 9th Street line, operating as a through route between those endpoints. Capital Transportation explained that the after Christmas period was selected for the inauguration of changes because that period was normally one of the lightest of all travel periods.

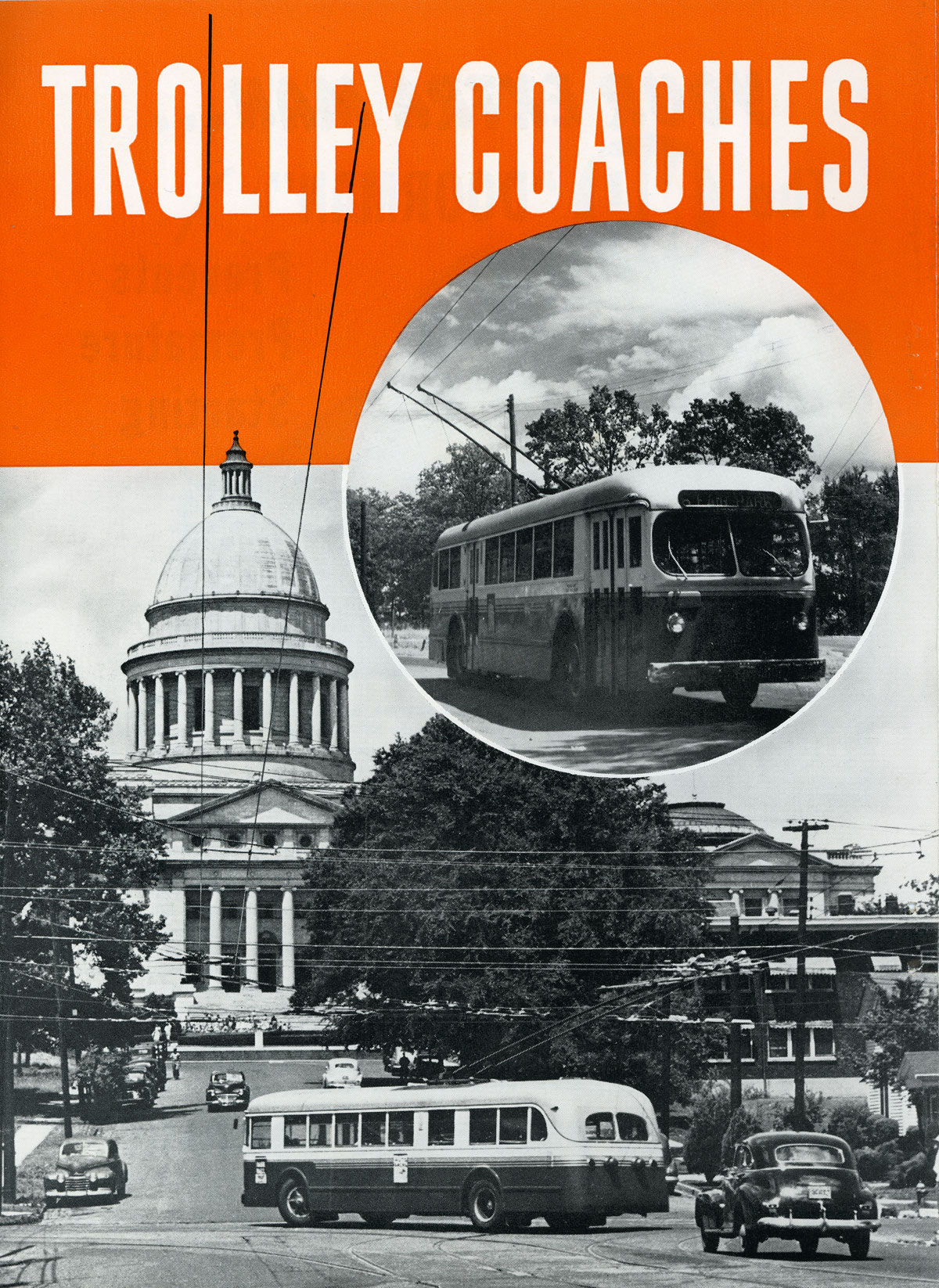

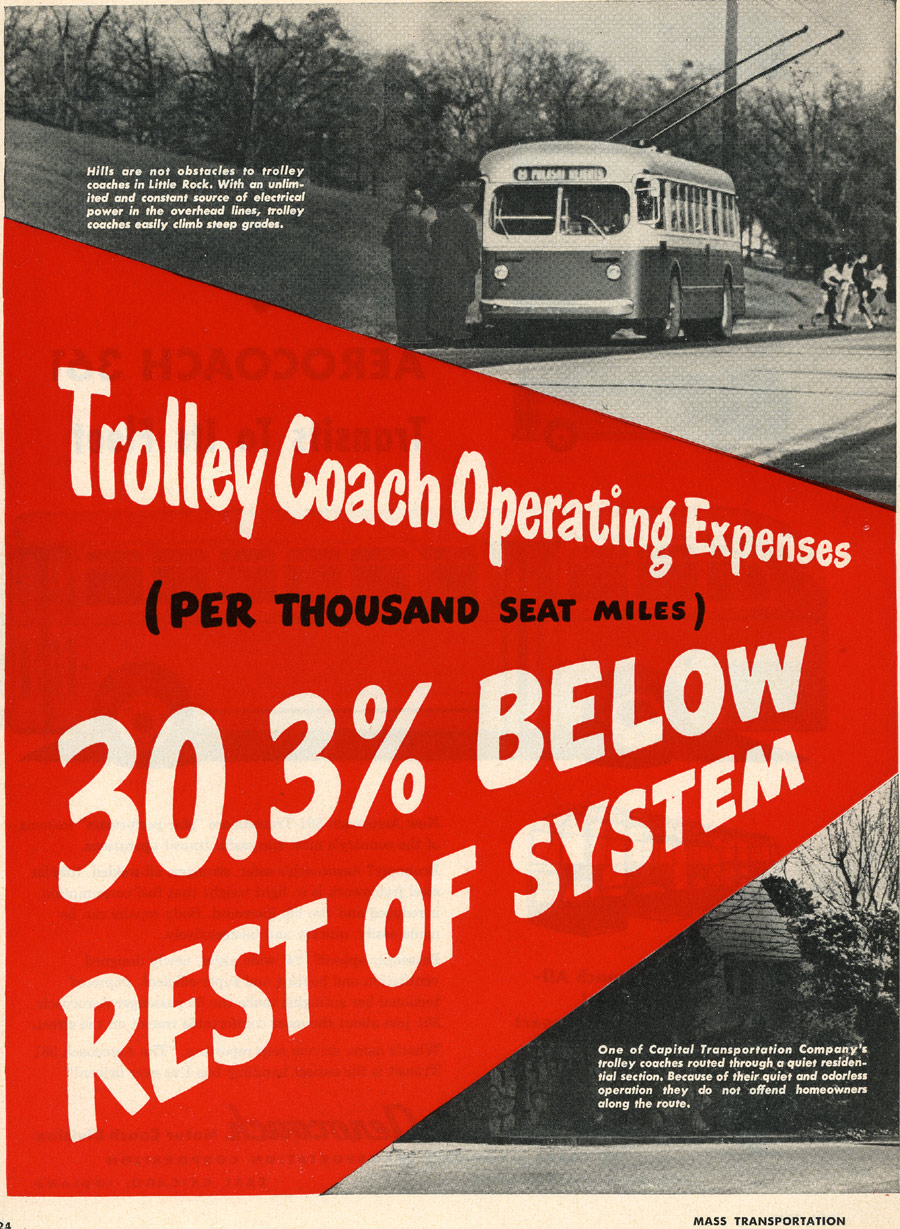

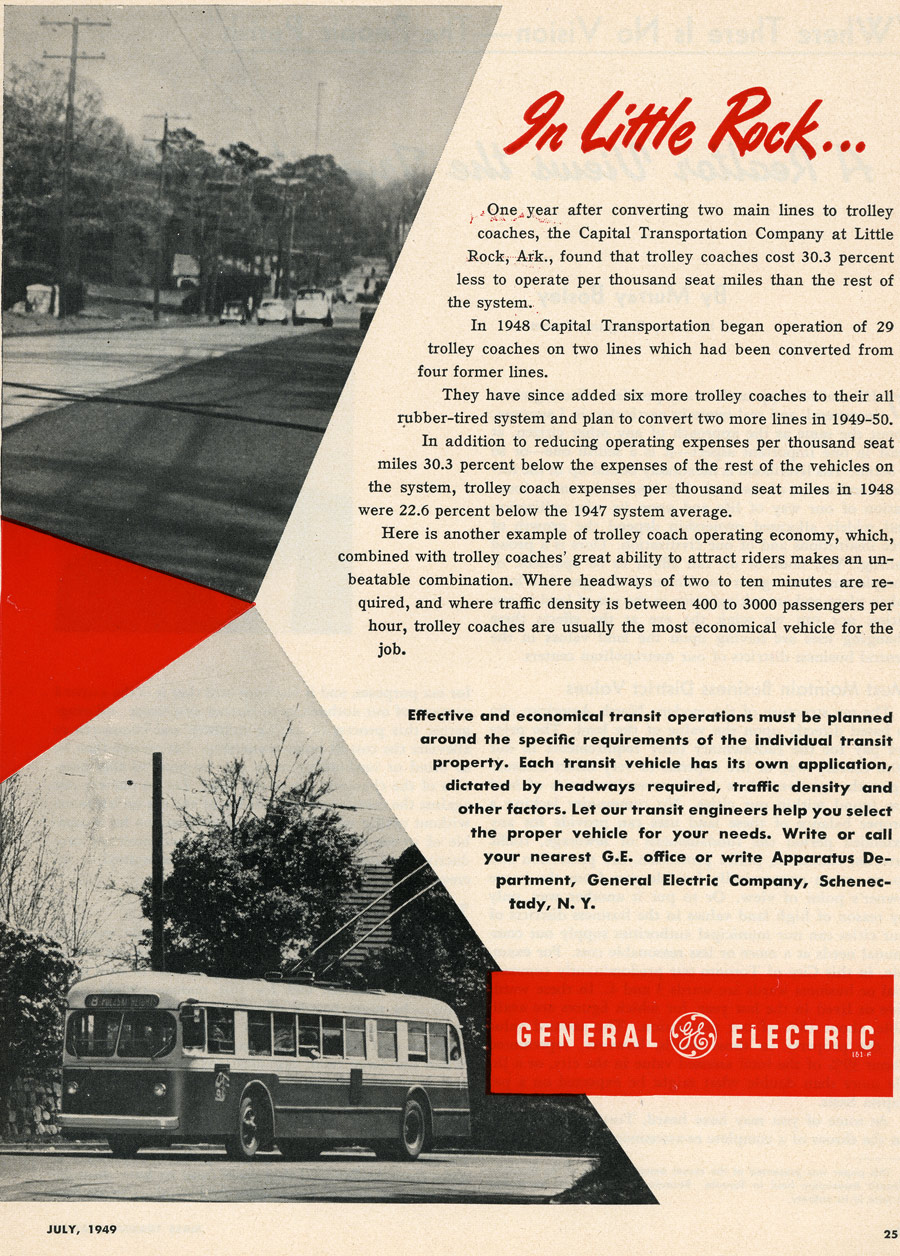

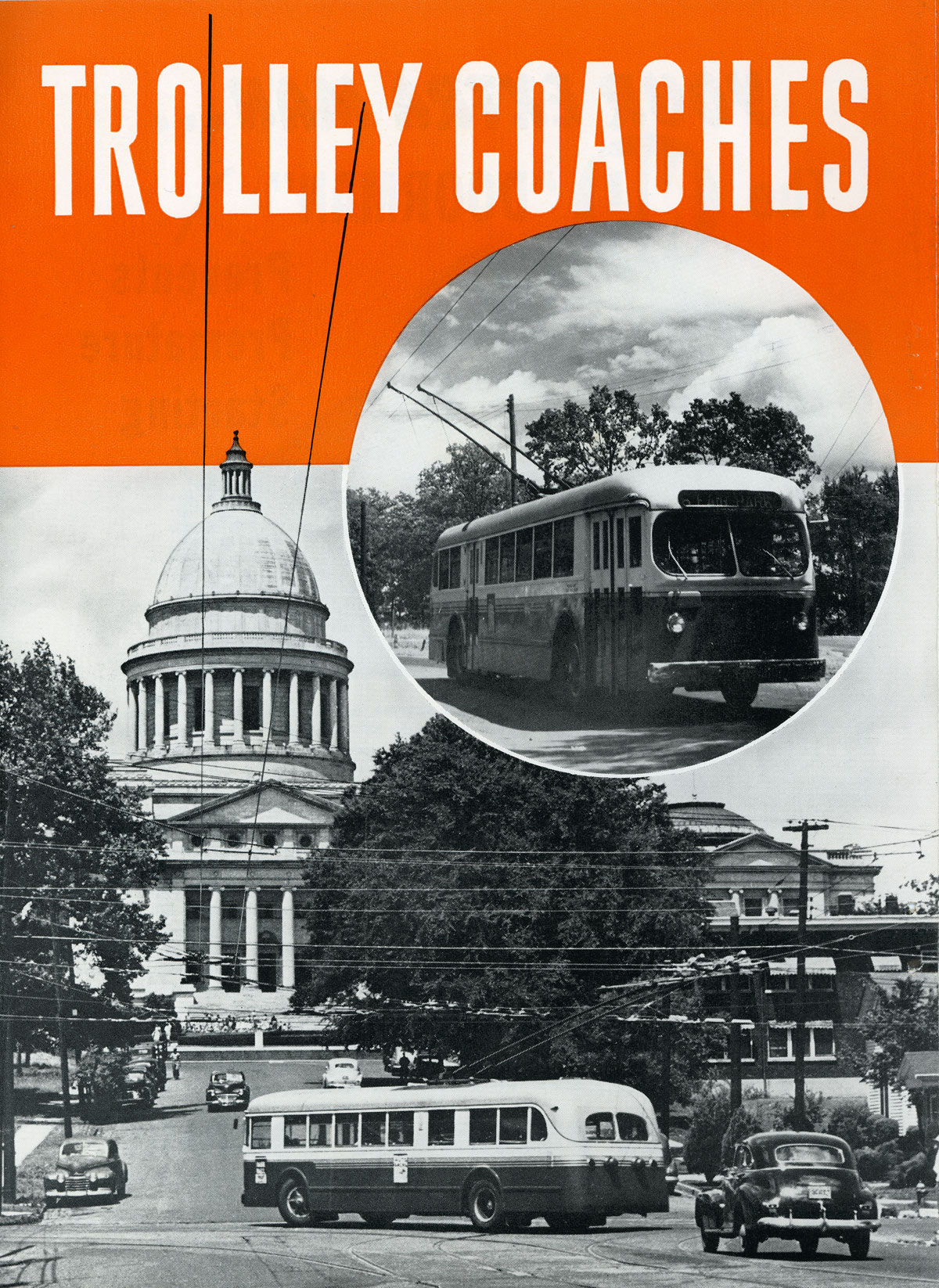

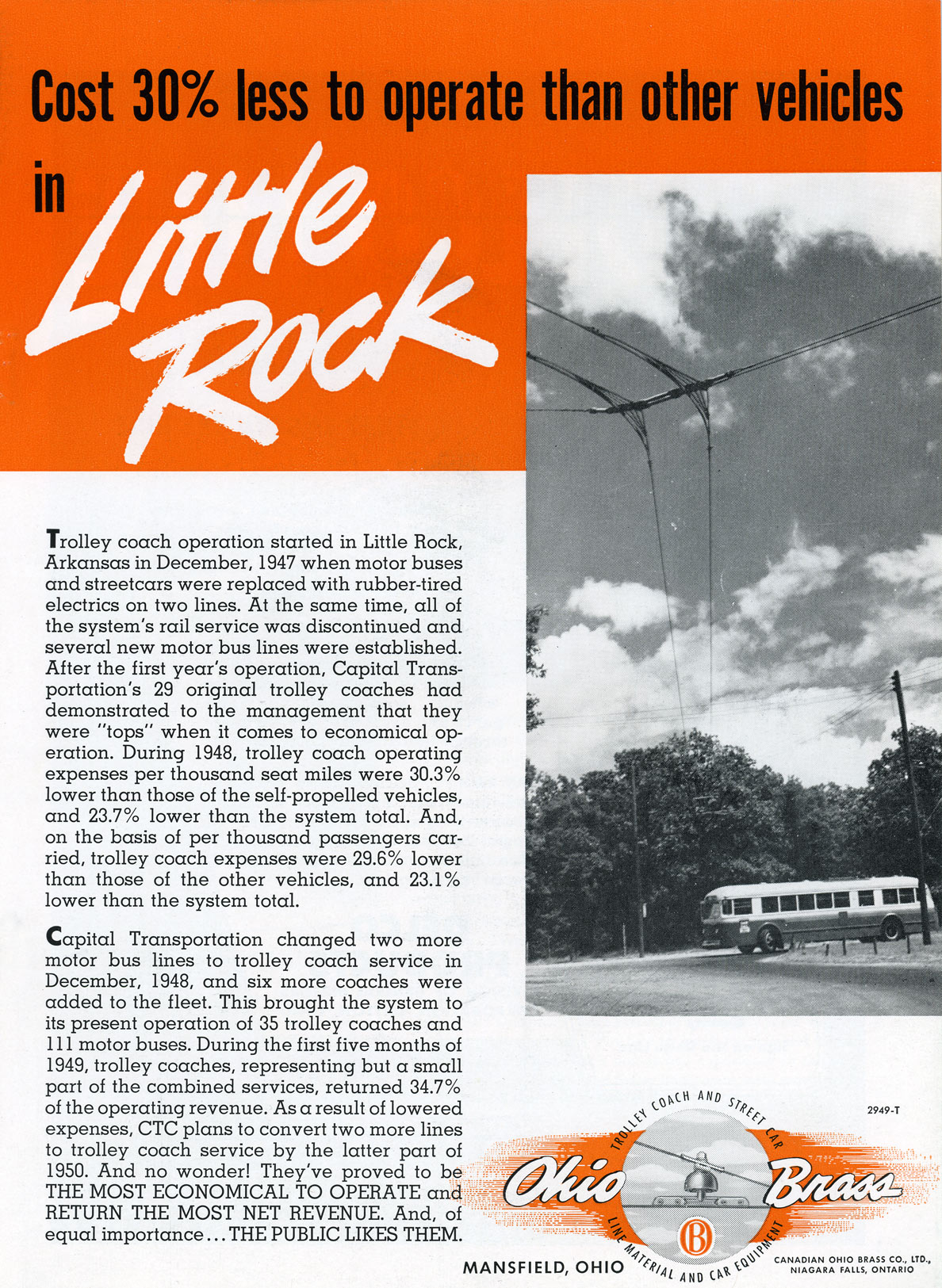

The Little Rock trolley bus installation was prominently featured in 1949 advertising by several manufacturers who provided hardware for the electric bus operation. Ohio Brass had long been a supplier of many components such as wire hangers, insulators, etc. for the overhead wire system of trolley cars, and they quickly transitioned into a similar supply role for cities utilizing trolley buses. General Electric provided many of the electrical parts for the actual trolley buses, and they likewise promoted the benefits of electric buses over internal combustion vehicles.

This Ohio Brass advertisement appeared in the October 1949 issue of Mass Transportation, a monthly trade journal of the transit industry. Similar ads appeared in other trade publications and in the December 1949 issue of The American City. The trolley bus in front of the Arkansas Capitol is westbound on the Fair Park line (Route 6), turning south on Victory Street. Note the streetcar tracks still visible in the street, and also the unusual camera angles which make sure to feature the overhead wire fittings manufactured by Ohio Brass.

The General Electric ad appeared in the July 1949 issue of Mass Transportation, and like Ohio Brass, highlighted the success of the Little Rock conversion, where the trolley buses were carrying a significantly larger percentage of passengers compared to internal combustion buses, and they also had lower operating costs. Both ads mention that Capital Transportation planned to convert two more internal combustion bus routes to trolley bus operation in 1950. Those two lines, the South Highland and West 15th Street lines would have been another substantial expansion of electric bus operation, perhaps enough to push conversion of most of the remaining Capital Transportation network to electric buses. Unfortunately, other events intervened, and that conversion was never made.

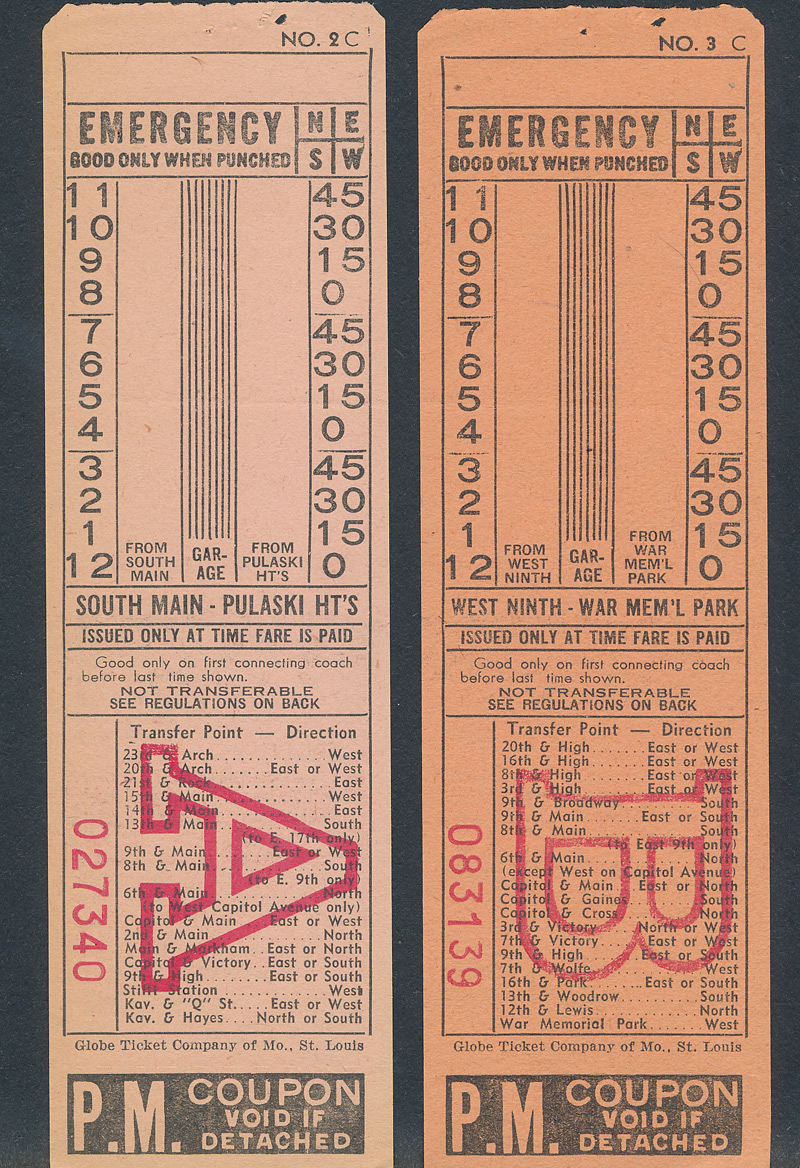

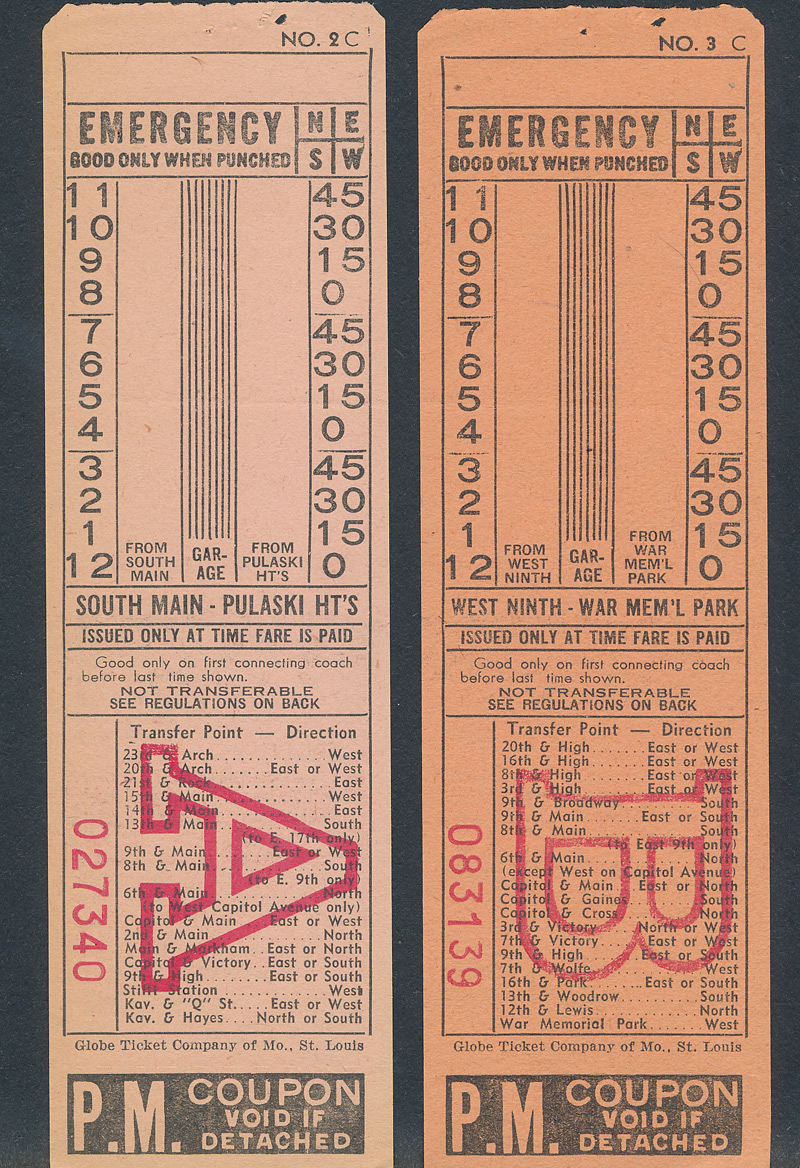

For transit riders, transfers were a normal part of day to day trips if it was necessary to connect from one line to another. Depending on the company, transfers were provided for free or for a nominal fee if requested when paying original fare. The transfer slip would then provide proof of fare payment when the passenger boarded the trolley bus or diesel bus on the connecting line. Transfer points were noted where lines crossed, and there were often restrictions on which directions of travel were allowed on a transfer. There was also a time component marked on the transfer, the intent being that passenger would use it for a continuous trip, not disembark, shop for an hour or two, and then board another coach to continue their trip - a scenario which in the company's view would require two separate full fare payments.

These transfers were for the South Main-Pulaski Heights route, and for the West Ninth-War Memorial Park routes. Although undated, they would have been used in the 1948-1951 time period, before the company name was changed to Capital Transit.

Perhaps foreshadowing present day efforts by the Arkansas legislature to extract road use fees from electric vehicles not otherwise paying a gas tax, the transit agency suffered an adverse ruling in June 1950 when the Arkansas Supreme Court reversed a previous decision by Pulaski Chancery Court. The lower court had ruled that the transit company did not have to pay yearly fees on electrically powered buses because Act 115 of 1939 authorized a tax only for gasoline powered buses. The Supreme Court disagreed and ordered Capital Transportation to pay about $6,000 in state license fees annually on its fleet of 35 trolley buses.

In December 1950, Courtesy Transportation (a new Arkansas corporation) and AP&L sought permission from the Arkansas PSC to let Courtesy buy Capital Transportation. Courtesy took over operations on a lease basis while the lengthy approval process went through PSC hearings. In October 1952, the PSC approved the sale by AP&L to Courtesy Transportation, and also the lease of the property to their newly formed affiliate, Capitol Transit. During 1952, the first evidence of reversing the electric trolley bus program appeared with the sale of four trolley coaches to Shreveport. Capitol Transit 600, 603, 605 and 607 became Shreveport Transit 428-431. Perhaps the purchase of 13 GMC TDH-4500s diesel buses in early 1952 helped to persuade the company that these trolley buses were surplus.

Trolley bus 605 pauses at the corner of Capitol & Pulaski in September 1953. The attractive red and cream paint scheme of Capital Transportation has been replaced with Capitol Transit's simpler orange and white scheme that was less expensive to apply and to maintain.

From December 1948 until March 1, 1956, four trolley bus routes were operated in Little Rock. Thanks to the good observation and sharp memory of the late John Mills, we have detailed descriptions of these routes. Thsee descriptions are from correspondence from John to the author in 2005.

- The Pulaski Heights (No. 8) route, starting at 5th & Main, ran north on Main to Markham, then turned left and continued west on Markham to Victory, then south on Victory to 3rd, then west on 3rd, following the old street car line out 3rd Street to Kavanaugh, then followed the old street car line along Kavanaugh to Kavanaugh and Hayes St. Trolley wire was continued from Hays on west to McKinley Street, where a new turn around loop was established. The street car line had previously ended near Kavanaugh and Hays Streets. The return to 5th & Main was via the same route.

- The Pulaski Heights and South Main routes were paired, in that an inbound trolley coach from the Pulaski Heights line would become an outbound coach on the South Main line at 5th & Main. The South Main route ran south on Main St. to about 22nd or 23rd street and turned west. I don't recall how far west the trolley wires continued before turning south for a few blocks and then turning back east to Main street on about 24th street, before turning north on Main street and returning to 5th and Main. The old street car line on the south end of Main had gone further west on 23rd St. to Ringo and made a loop south across Roosevelt Road a couple of blocks then turned back east to Arch, back to 23rd, and then east to Main Street. This part of the street car line had been discontinued several years earlier and the route shortened. By the time the trolley buses replaced street cars, the line did not cross Broadway to the west.

- Starting again at 5th & Main, the Fair Park (No. 6) route went west on Capitol Avenue to Victory, where it turned south to 8th St., then west on 8th to Wolfe, south on Wolfe to 11th, west on 11th to Park, south on Park to 13th, west on 13th to Lewis, then north on Lewis to 11th, west on 11th to where the street car private right of way began leading into Fair Park and terminating at the Travelers Field baseball park. The private right of way portion of the old street car line had the tracks removed and paved over for the trolley buses to operate on this portion of the route. After turning around in front of the baseball park, the same route was followed back to 5th & Main.

- Like the Pulaski Heights and South Main routes, the Fair Park and West 9th street routes were paired, changing from one route designation to the other at 5th and Main. The West 9th Street line continued south on Main to 9th St. Turning west on 9th St., the route went west to High St. where it turned south and continued to about 34th & High, returning to 5th & Main via the same route. The old South Highland (No. 7) street car line did not get trolley buses, but was replaced by an alternate bus route that went west on 14th St. to Woodrow, then followed the old street car route as far as Cedar Street, then south to Roosevelt & Lewis.

- At 13th & High, on the block over to 12th & High and east over one block, a new trolley bus maintenance facility was built for the new trolley buses. Wires were also strung on Victory between 3rd and 5th, so that trolleys from both routes could operate as specials to Little Rock High School. The electric trolley coaches were beautiful pieces of equipment, and the ride was excellent. Due to their weight, travel on snow and ice was no problem.

Meanwhile, all was not well with the Little Rock transit operation. Ridership was falling dramatically, and unionized employees wanted cost of living adjustments. Division 704 of the Amalgamated Association of Street, Electric Railway and Motor Coach Employees went on strike June 1, 1951, after Capitol Transit denied their request for a wage increase. Capitol Transit quickly agreed to the wage increase, but went to the Arkansas PSC to get a rate increase to 10-cents for adult fare and 5-cents for a transfer. When the PSC agreed, the strike ended and normal operations resumed.

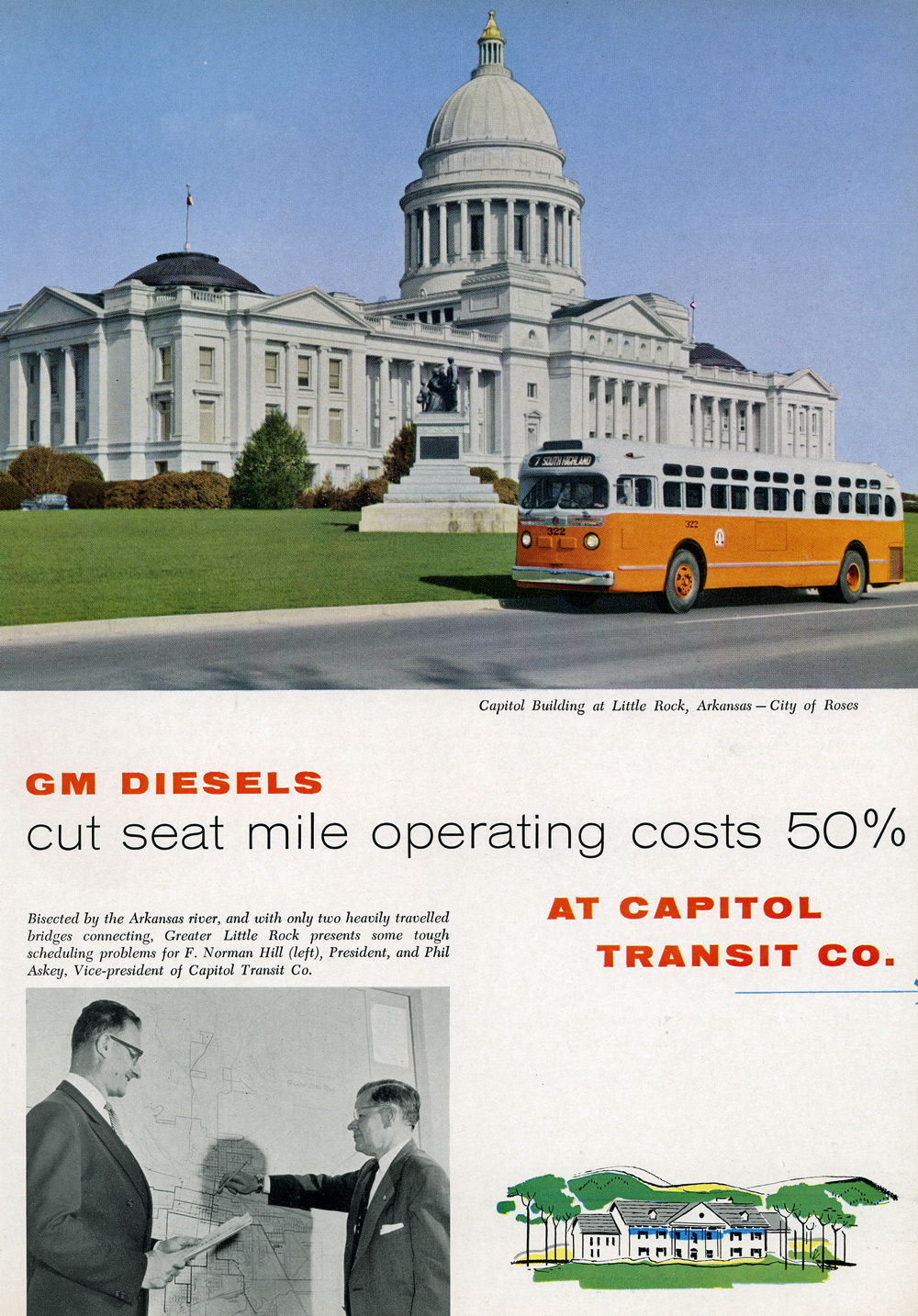

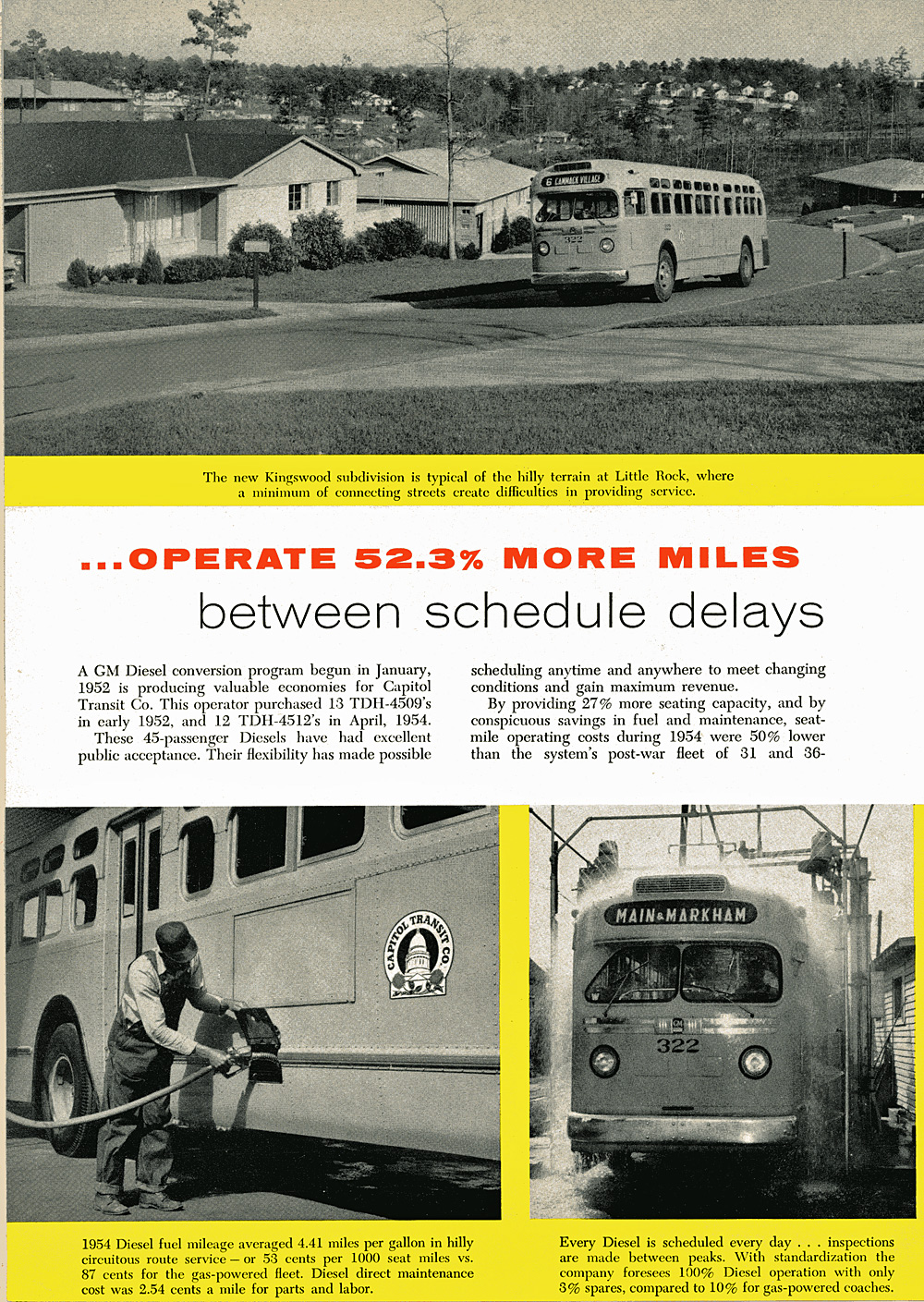

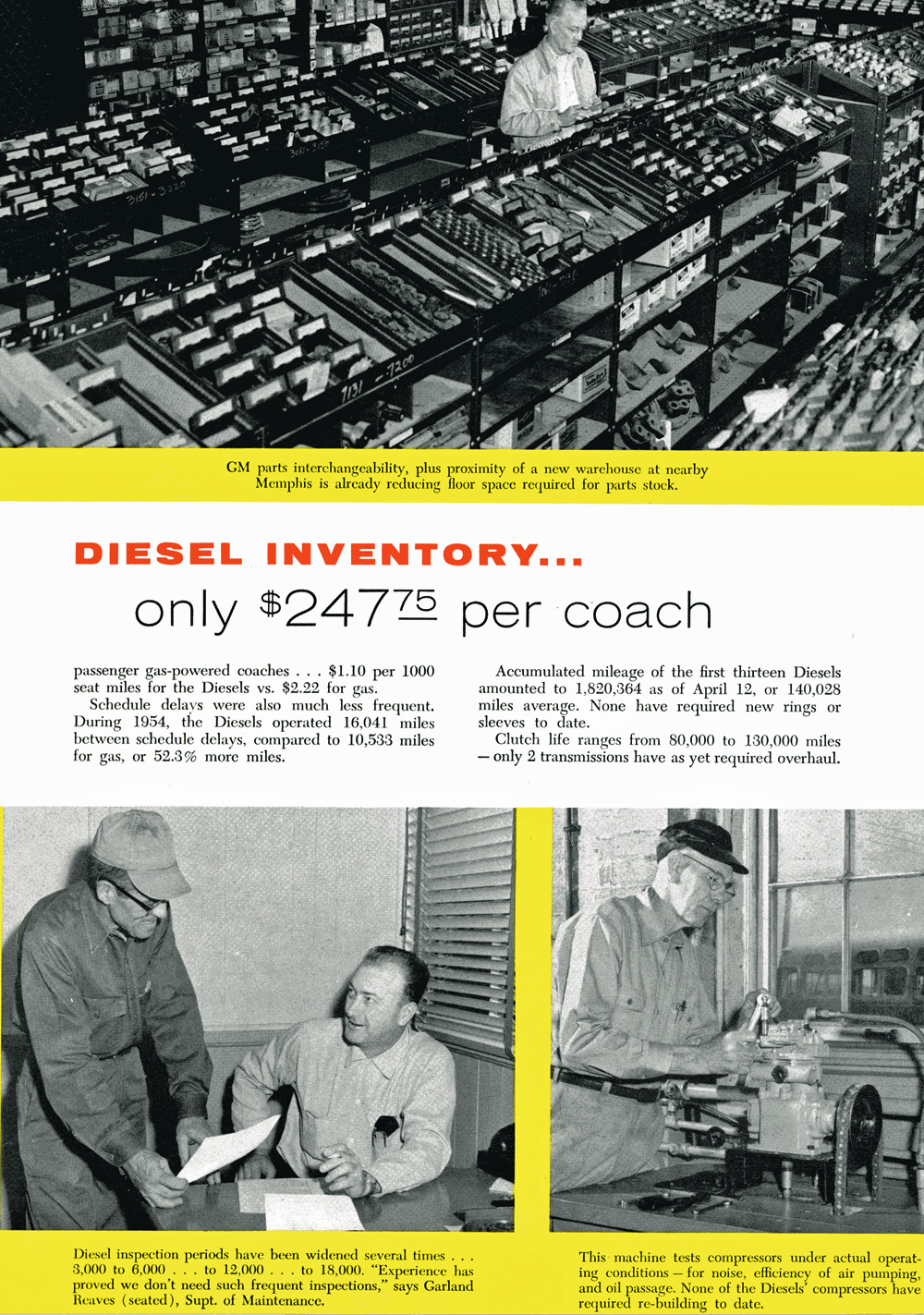

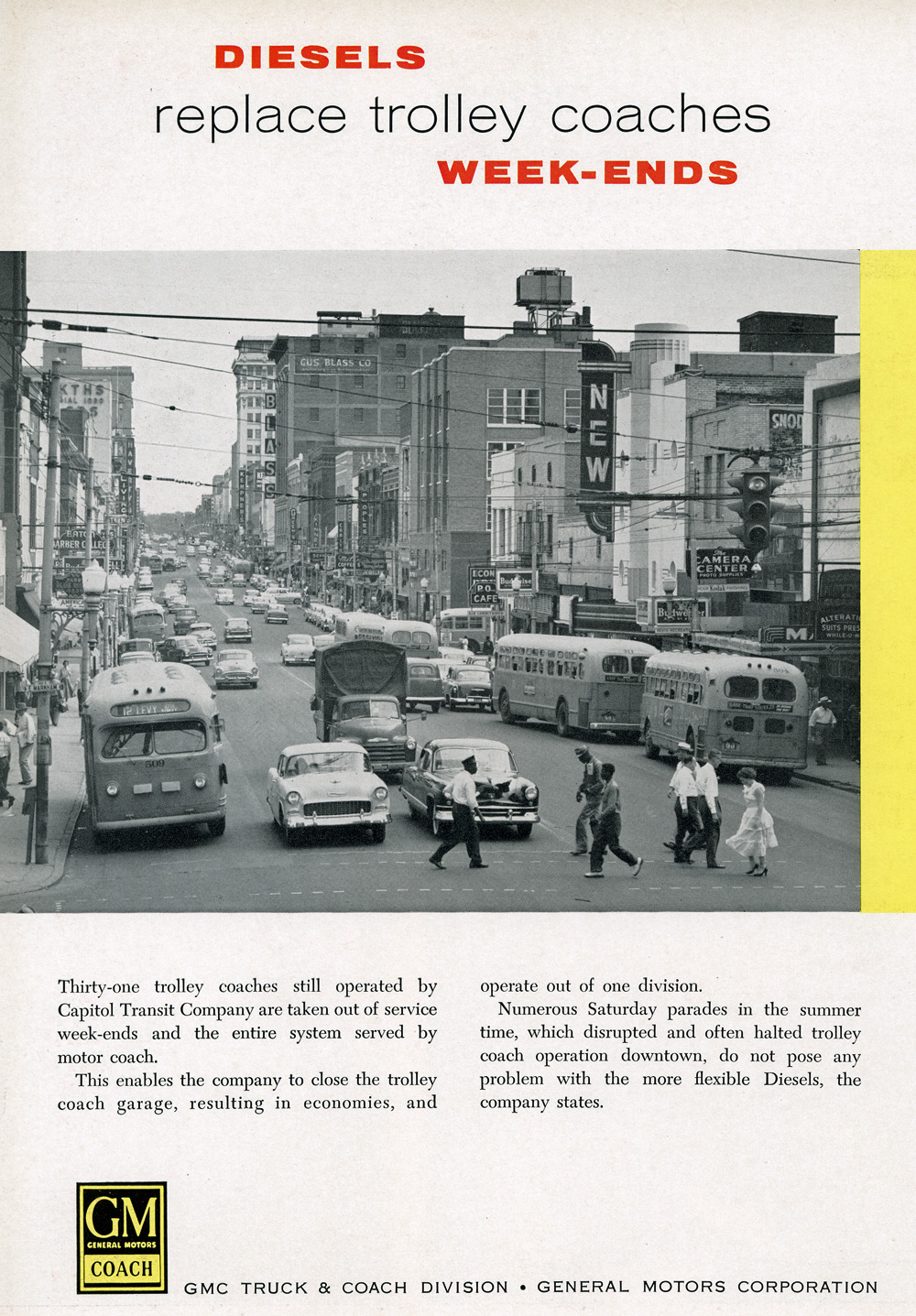

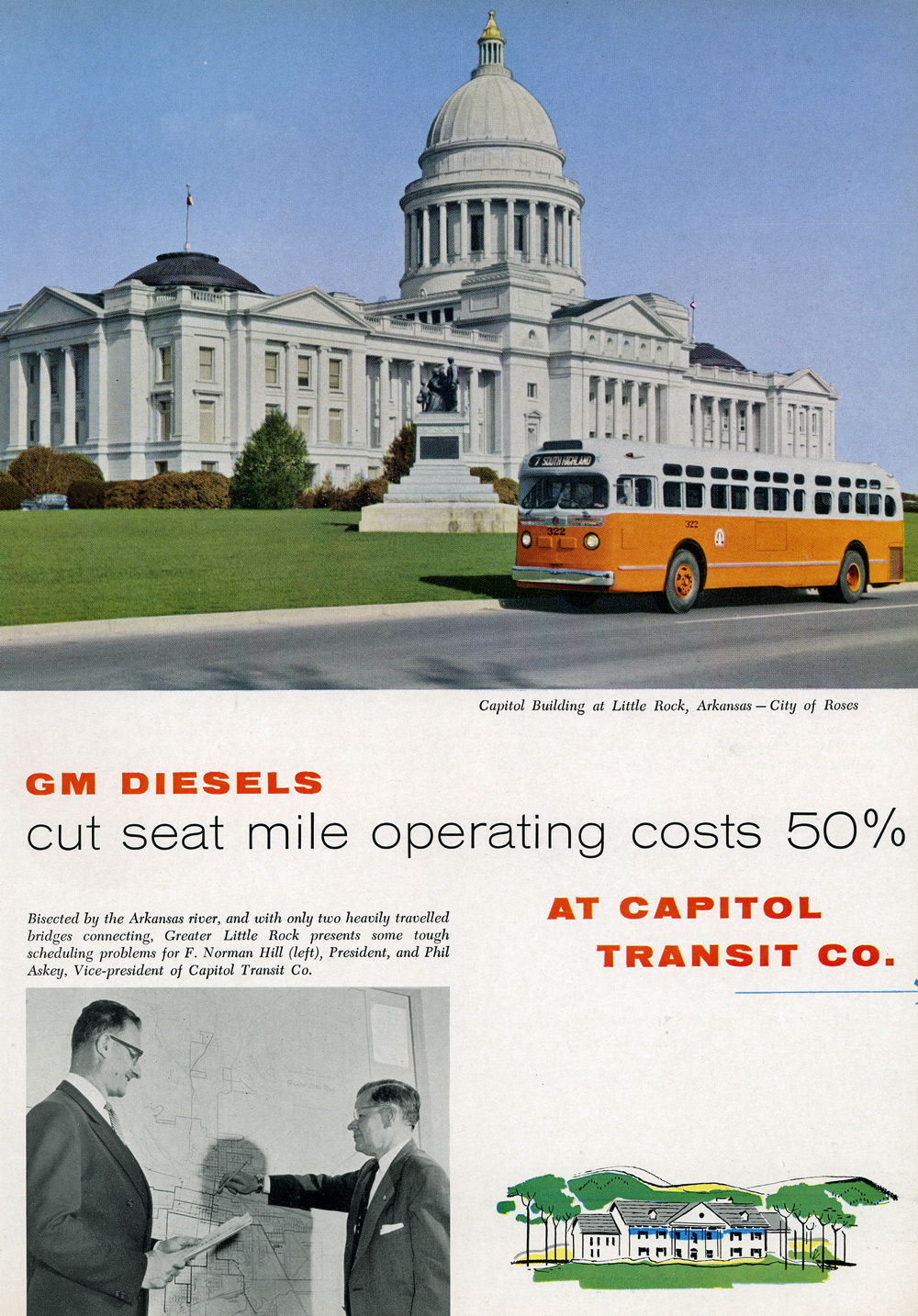

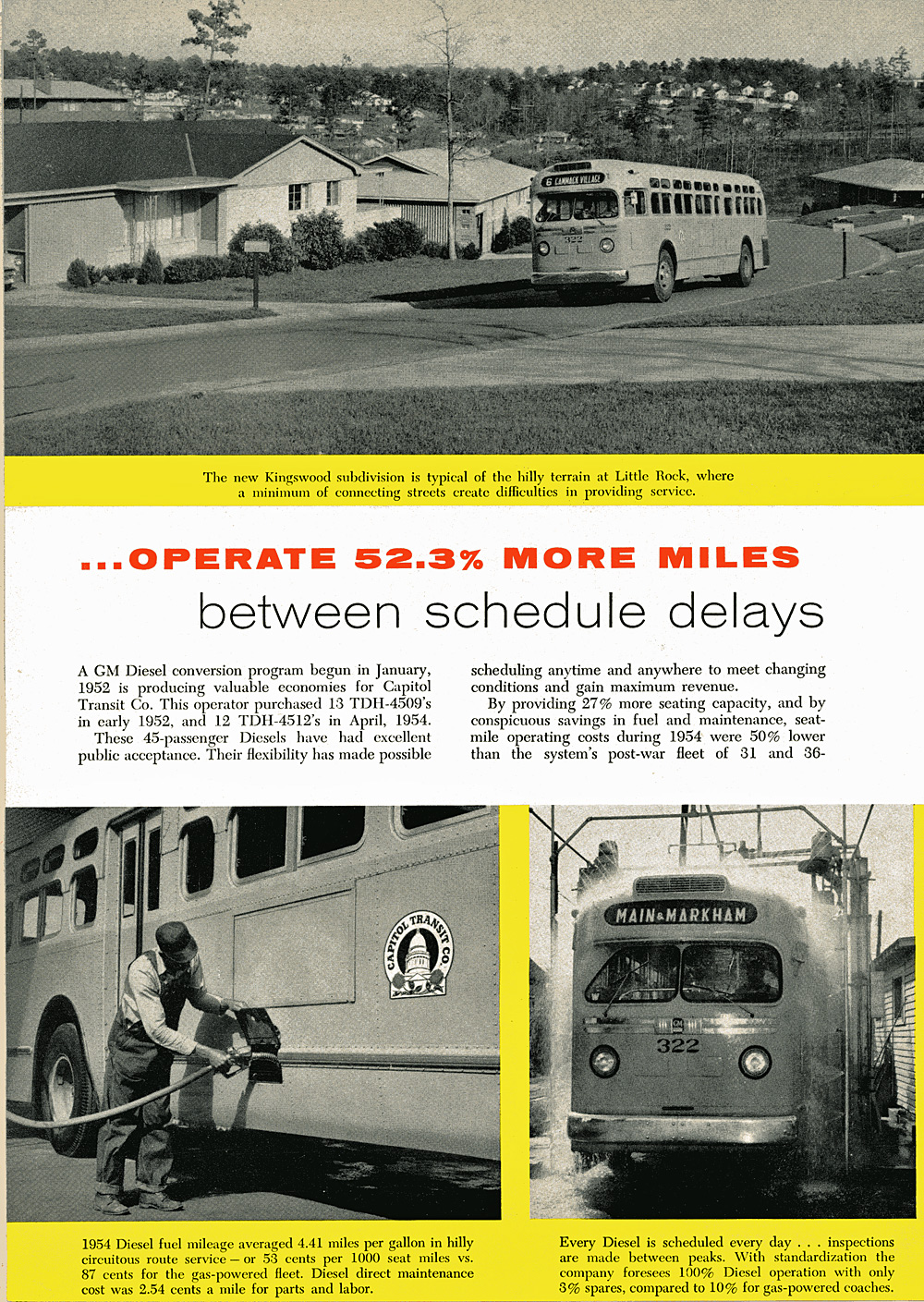

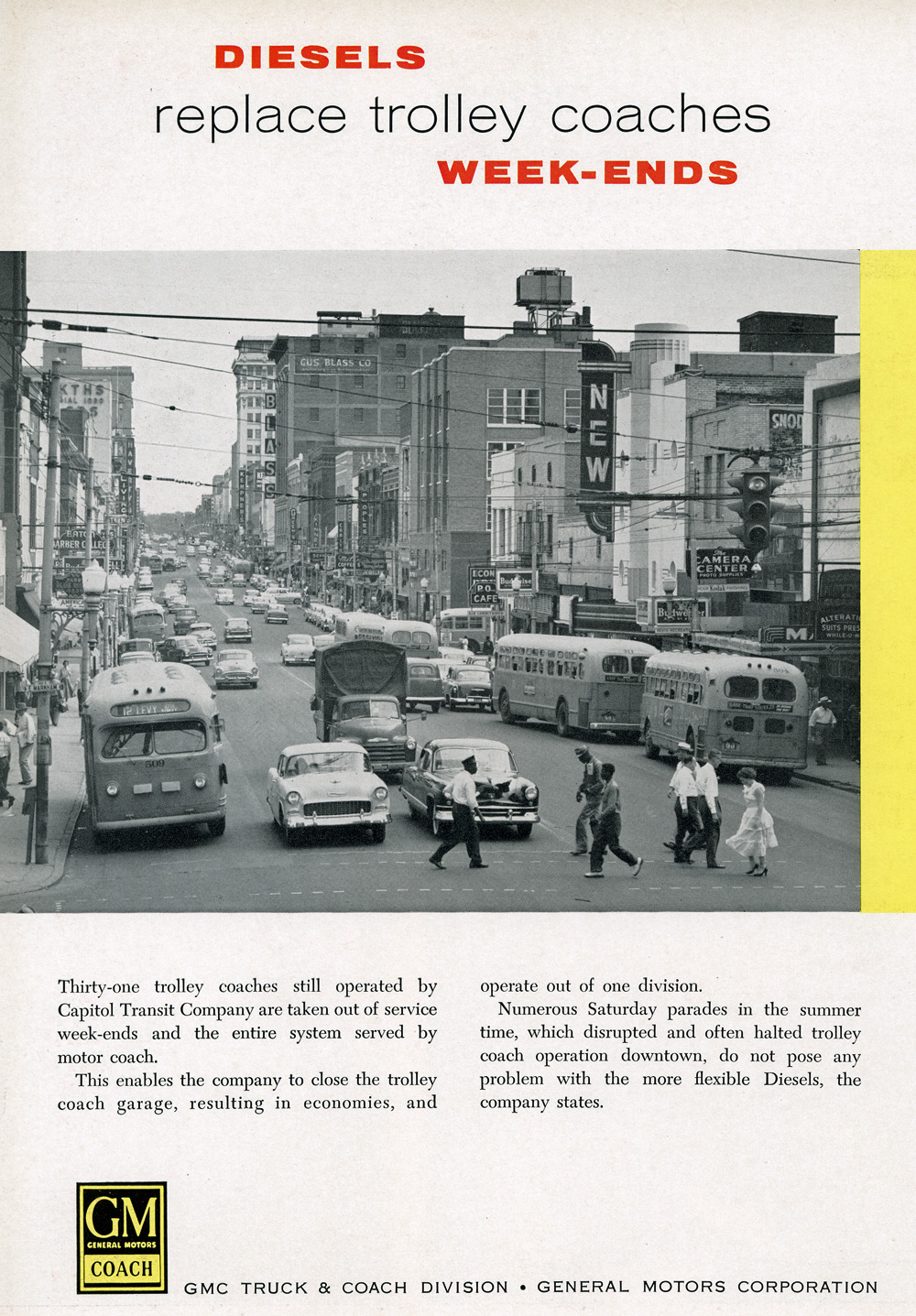

This circa 1955 General Motors Corporation advertisement shows the new color scheme of orange and white that was adopted by Capitol Transit in the early 1950s. The advertising offers favorable comparisons of the relative maintenance and operating costs of diesel buses versus gasoline buses. Notably absent is a comparison of similar costs versus electric trolley bus costs. The ad does note the then current policy of Capitol Transit to shut down electric bus operation on weekends, thus allowing the closure of the separate trolley bus garage.

Several suits were filed by the City of Little Rock over failure of Capitol Transit to pay street repair fees as prescribed by the franchise, although the transit company argued that some of the fees being demanded were for damages to curbs and gutters having nothing to do with bus operations. Labor problems continued as Division 704 continued to press for wage increases with each contract renewal, and ridership continued to fall. From 1953 to 1954, ridership fell by over 2 million passengers, to a level of 15 million riders, versus over 35 million carried 10 years earlier. The company's deteriorating financial condition and declining ridership prompted service cutbacks and employee layoffs, fueling more dissatisfaction. The company's financial report for calendar year 1954 showed a loss in excess of $75,000.

On June 22, 1955, Local 704 called a strike, Capitol Transit responded by hiring non-union replacements which allowed some service to continue. Unable to secure a full compliment of drivers and mechanics, the company ran buses only along the busiest routes and ceased evening service altoghether. The union responded by offering free jitney service, 150 to 200 private cars picking up passengers along bus routes, in an attempt to win public support. The strike grew increasingly volatile as tempers flared between union employees who were infuriated by the "scabs" that the company had hired to replace them. Several episodes of violence occurred whenever the company attempted to start evening service again, including at least two attempts (one successful) of throwing dynamite into a bus.

When the City of Little Rock officials refused a request for a fare increase in January 1956, Capitol Transit served notice that they were surrendering their franchise. A new company, Citizens Coach Company, was formed with heavy financing from the union national office, receiving the Little Rock transit franchise on January 31, 1956. Capitol Transit operated the system through February, but discontinued all service including trolley bus service, on March 1. Citizens Coach did not acquire any Capitol Transit equipment, but instead purchased an 8-year old fleet of used buses and sent newly hired union drivers to Toledo, Ohio, to pick up the buses and deliver them back to Little Rock where they were stored at the Arkansas State Fairgrounds until the start of Citizens Coach operations. It appears that these circa 1949 Transit model 91 buses retained the red and cream colors of Detroit's Department of Street Railways. Citizens Coach began operations on March 2, 1956, with 130 drivers and 35 mechanics, the majority of whom were union members.

Fred Worden, an experienced transit manager from various Illinois and Wisconsin companies was selected to be president and general manager of Citizens Coach Company. Worden believed that he could reduce expenses by not having to operate trolley coaches or having to pay leasing fees that Capitol Transit was incurring for equipment. He cited a cost of 72-cents per mile for trolley coach operation versus 45-cents per mile for internal combustion buses. The source of that comparison is unknown, but likely was derived from GMC data produced to help sell GMC buses. Capitol Transit, which had apparently already decided to go with diesel buses, had purchased 13 new buses in 1952 and 12 more in 1954. All of the newest diesel buses, 10 older diesel buses, along with the trolley buses and most of the overhead wire fittings were quickly sold to other operators. Shreveport purchased 14 more of the ACF-Brill trolley coaches, while Dayton (Ohio) City Transit purchased 11 of the ACF-Brill trolley coaches and all six of the Marmon-Herrington trolley coaches.

Thus ended the brief period of trolley bus operation in Little Rock. Finances of several later transit operators were increasingly bleak, and it was finally realized that if transit was to survive in Little Rock, it must be treated as a public utility. Following Citizens Coach Company came Twin City Transit, the last relatively private transit operator. After TCT, Central Arkansas Transit arrived on the scene, an operating company managing the transit system that was actually publicly owned by Metroplan. A limited streetcar system reappeared during CAT's tenure, known as River Rail. In recent years CAT has rebranded itself as Rock Region Metro, providing transit service to 10,000 riders each day.

Trolley coach routes superimposed on circa 1983 Little Rock map.

Trolley coach routes superimposed on circa 1983 Little Rock map.

Sources:

- Motor Coach Age July-August 1986

- Victory Based on Violence is Undesirable - the Little Rock Bus Strike of 1955-1956, by William Jordan Patty - Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Autumn 2002

- personal correspondence and documents

- Trolleybuses

Return to Arkansas Railroad History Home Page

Trolley coach routes superimposed on circa 1983 Little Rock map.

Trolley coach routes superimposed on circa 1983 Little Rock map.