The L&A-KCS neon sign on the railroad's Rampart Street station in New Orleans in the 1940s included an airplane, an optimistic vision that would prove to be premature.

The idea of expanding into air transportation was not lost on the progressive management team of the Kansas City Southern. At the annual stockholder meeting in Kansas City on May 9, 1939, Harvey Couch, chairman of the board, announced that the KCS was proposing to establish a direct mail, passenger and express airline route between Kansas City and New Orleans. Couch noted that this was not an "overnight thought" but that when the Louisiana & Arkansas Railway had been reorganized in 1929, a provision was placed in the original charter granting that road the right to operate an air service as well as a bus service if desired. "We were looking toward the future of air travel then, and we believe that now is the time to step into the air transportation picture," the chairman said. Developing the proposal for the new air route was made the responsibility of W.N Deramus, who at that time was executive vice president of the railroad. News accounts identified this KCS proposal as one of the first moves on record in which a railroad recognized the growing importance of air transportation and sought to create an overhead service paralleling their railroad, in this case between Kansas City, Fort Smith, Texarkana, Shreveport, Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

In 1938, President Roosevelt had signed into law the Federal Aviation Act, which established the Civil Aeronautics Authority. This independent regulatory agency provided the classic public utility type regulation over the developing air transport industry. At the time of the KCS announcement, the CAA was completing a national survey of existing air transportation routes to identify missing links in the nation's airline network. In making application for a certificate of public convenience and necessity, the KCS would have to establish that their proposed route would be economically sound and would fit into the airline network picture to the satisfaction of the CAA. The existing airline route from Kansas City to New Orleans was via TWA from Kansas City to St. Louis and then via Chicago & Southern to New Orleans, a considerably more circuitous routing. When the actual KCS petition was received by the CAA about six weeks later, Joplin had been added as another intermediate stop. The railroad told the CAA that it planned to purchase three 14-passenger Lockheed planes at a cost of $255,000. The actual application was made in the name of Kansas City Southern Transport Company, a railroad subsidiary which had operated a motor vehicle service since 1933.

On November 22, 1939, KCS officials and business and civic leaders made an aerial survey of the route using one of the Lockheed "Lodestar" planes planned for the route. The initial trip from New Orleans to Shreveport took about ninety minutes. C.M. Belinn, general manager of the proposed airline, reaffirmed plans to purchase three of the 220-mile-per-hour Lockheeds if the CAA petition was approved, as well as plans to locate airline shops and headquarters at Shreveport. Mid-Continent Airlines, Branniff Airways and Continental Airlines were also competing for the Kansas City-New Orleans route, with hearings scheduled before the Civil Aeronautics Authority in Washington, D.C. on January 22, 1940.

At the hearing, each of the carriers outlined their plans for service. KCS proposed two frequencies daily, with intermediate stops now including Joplin, Fort Smith, Tulsa, Muskogee, Texarkana, Shreveport and Baton Rouge. Both Braniff and Continental proposed one flight daily by way of Wichita, and Mid-Continent proposed one flight daily via Joplin and Bartlesville. KCS proposed to operate their schedule, including intermediate stops, in about 5 1/2 hours between Kansas City and New Orleans.

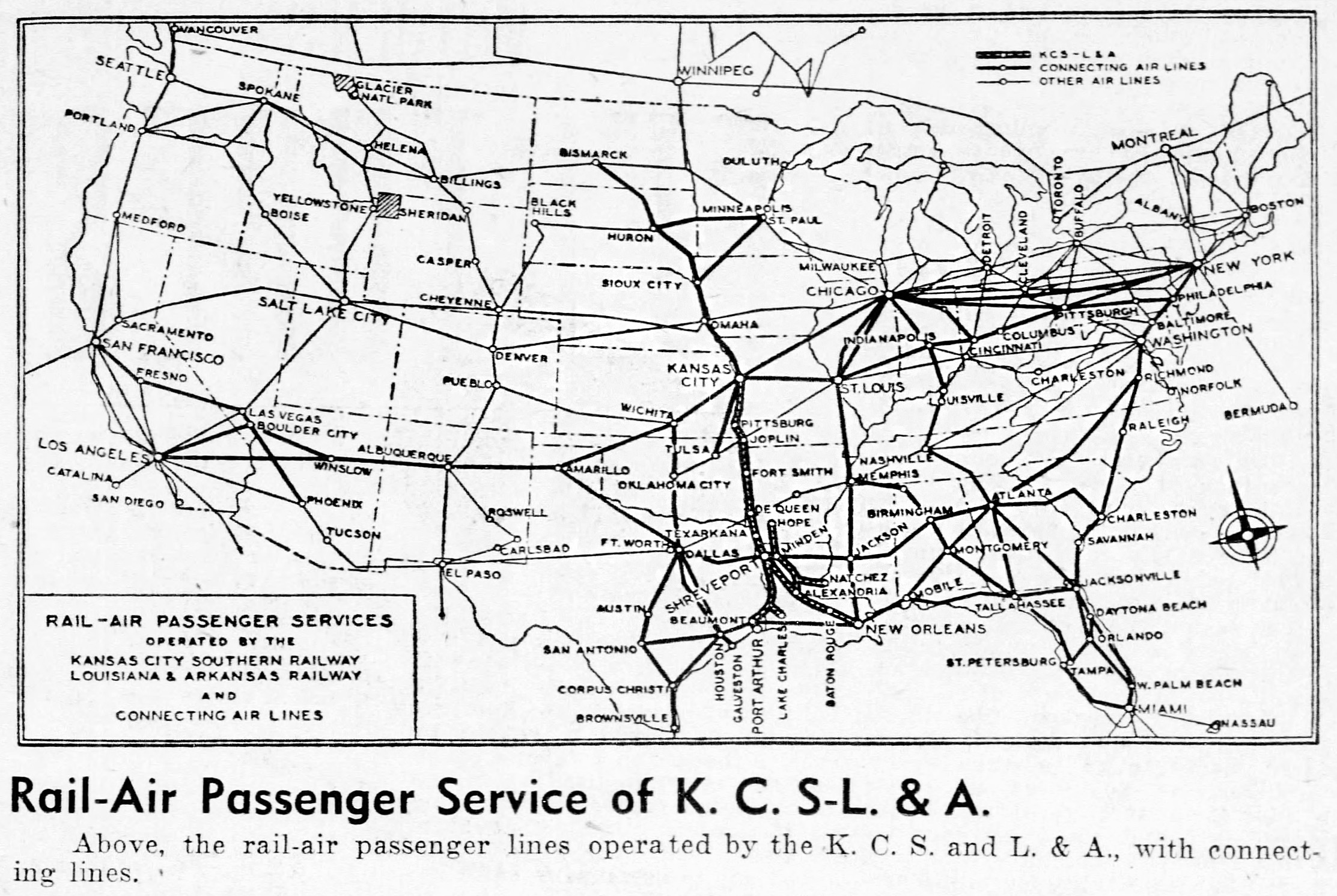

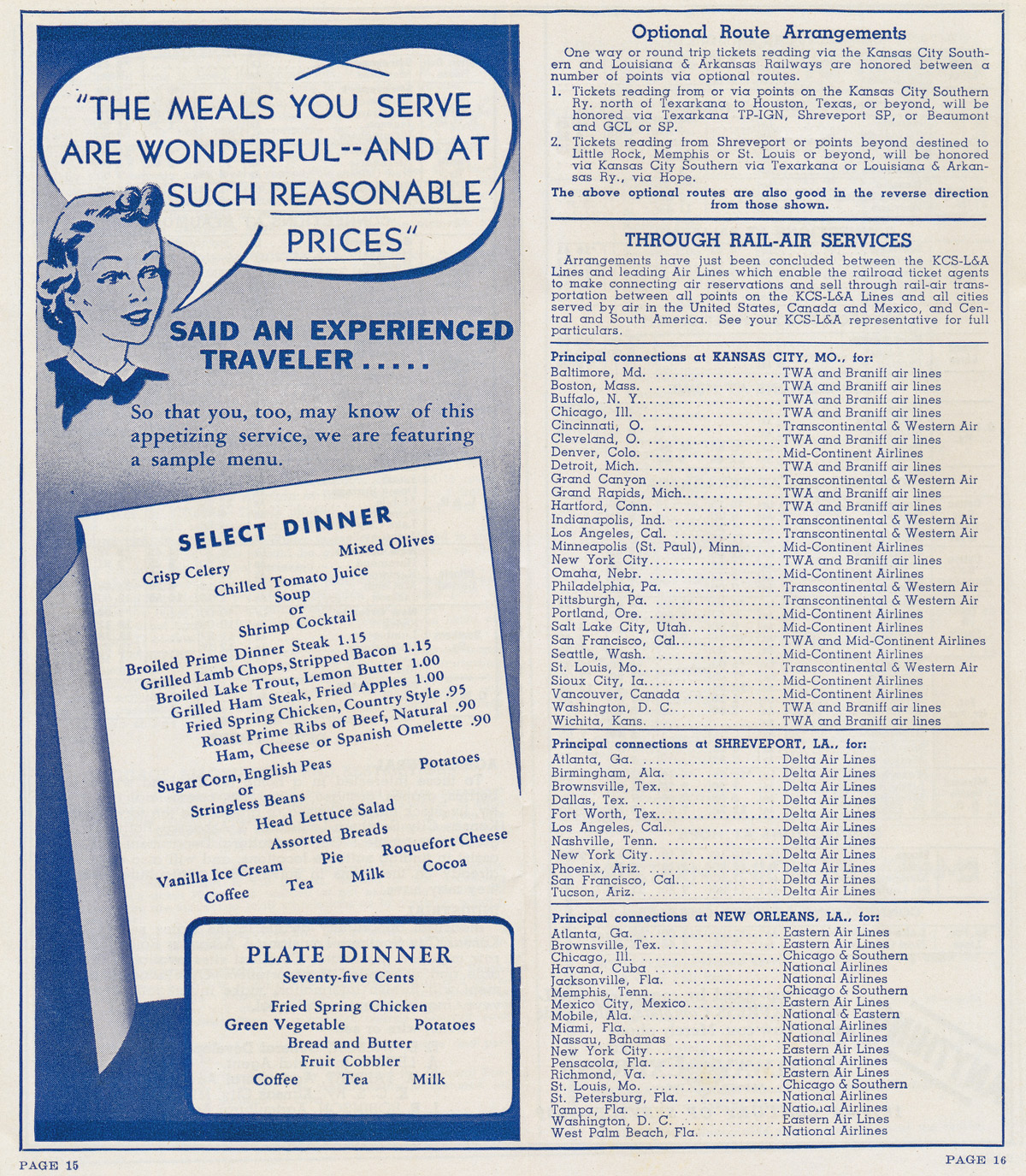

While awaiting CAA action, KCS in 1940 established an interline ticketing arrangement with numerous airlines in Kansas City, Shreveport and New Orleans. The premise was to encourage prospective passengers to ride existing KCS passenger service to one of those cities, and then transfer to a plane for a flight to the passenger's final destination. Every ticket office on the KCS thus became an interline ticket agency for the participating airlines, an arrangement said to save time for KCS patrons, but also one which would help familiarize railroad ticket agents with airline schedules and ticketing procedures. The program would also help build relationships between the KCS and airlines that would potentially be connections if and when KCS air service began. Although there was a focus on future air transportation by one part of the KCS, considerable attention was also being given to the existing rail passenger service, with announcements made in the summer of 1940 of a new streamliner, the Southern Belle, which was expected to begin service in September, after the opening of the new Mississippi River bridge at Baton Rouge. The KCS interline ticketing with air carriers seems somewhat convoluted when viewed today, but at the time, good highways were not well developed in KCS territory and for the most part, commercial aviation was something seen flying overhead - most KCS cities were truly "flyover country". Most travelers were still more comfortable with all-train routings, but the aviation angle was an interesting effort by KCS to capitalize on the public's growing interest in commercial aviation service.

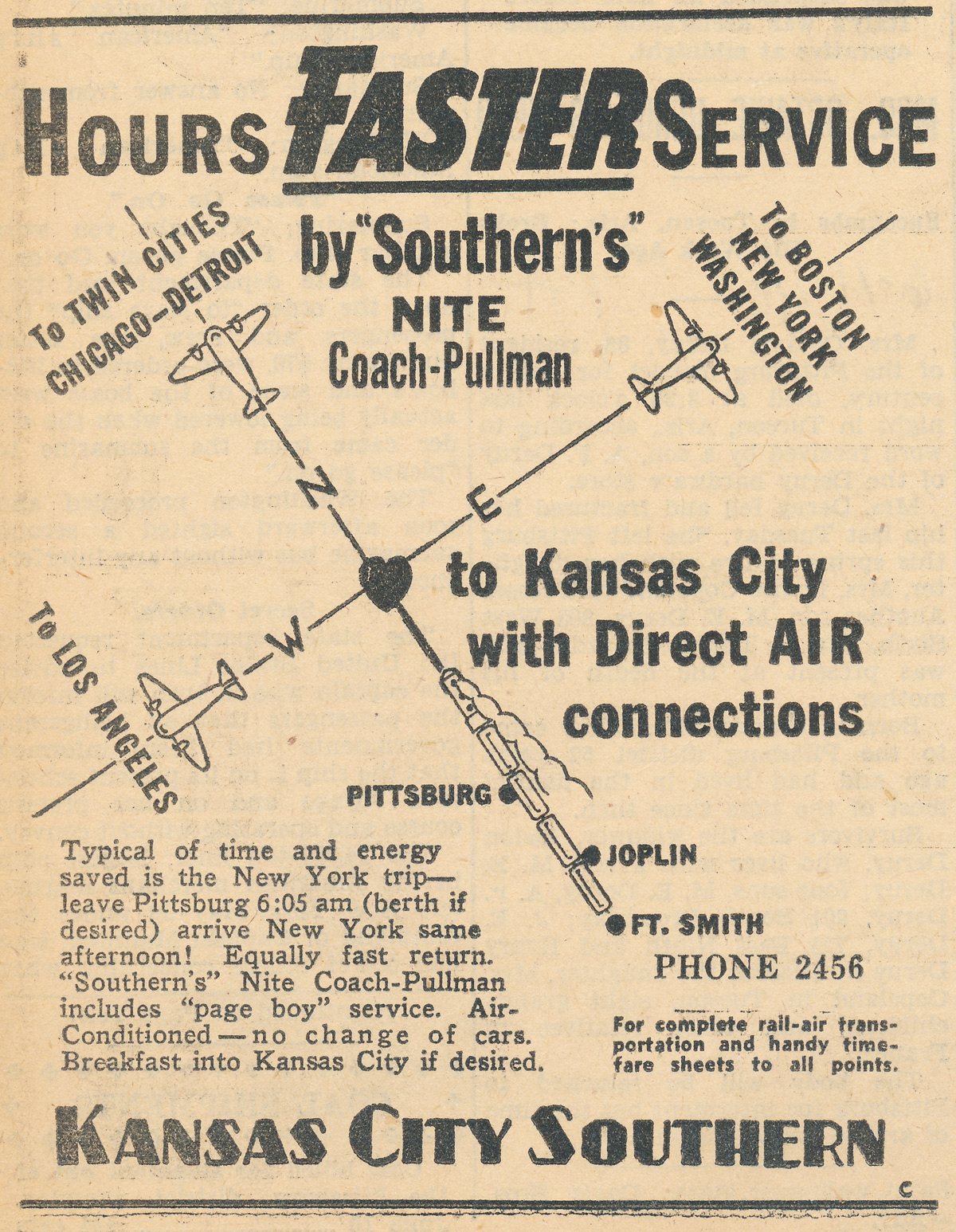

For three public timetable cycles, May 26, September 2 and October 13, 1940, KCS included a table showing which airlines offered flights from the three major aviation hubs on the railroad. At Kansas City, through tickets were available to connecting flights on TWA, Braniff, and Mid-Continent. Only Delta was available at Shreveport, while Eastern, National and Chicago & Southern were available at New Orleans. It is unclear how passengers made connections between the railroad station and airport in any of these cities. Did the ticketing include a transfer coupon, good for taxi or transfer bus, or were passengers expected to make their own arrangements? The new service was advertised in on-line newspapers, as illustrated by a variety of newspaper ads which appeared in the Pittsburg, Kansas paper in June 1940.

Airline connections first appeared in the May 26, 1940 KCS timetable, and subsequent issues were similar except for minor changes related to airline schedules. In all cases, the KCS was handling only a short segment of the trip, before handing the passenger off to a competing mode of transportation. On one hand, the KCS was likely receiving the same revenue for this passenger as they would be receiving from a passenger using an all-rail routing. However, it is an open question of how this arrangement was viewed by connecting rail carriers who were losing what would likely have been a high-revenue ticket, often with additional revenue from Pullman accommodations. Thus far, no reporting of the KCS intermodal interline effort has been found in the industry trade journal Railway Age, and thus no hint about a possibly unfavorable reception from other railroads.

In 1940, the Civil Aeronautics Board was formed as an offshoot of the Civil Aeronautics Administration, and in July, it was announced that the KCS proposal was being held in abeyance pending proof of citizenship of the stockholders of the parent company. The law required 75% of the voting interest of any airline be held by United States citizens, and it was known that Dutch interests were substantially represented in the ownership of the Kansas City Southern Railway. Although this hurdle was subsequently resolved, prospects for KCS air service were becoming increasingly doubtful. On December 21, 1940, the CAB formally denied applications of Kansas City Southern Transport as well as applications by Braniff and Mid-Continent for Kansas City-New Orleans service. The CAB initially ruled that existing traffic needs did not require new routes into New Orleans, although as wartime traffic increased, the route was subsequently awarded to Mid-Continent Airlines. This adverse Civil Aeronautics Board ruling ended any immediate plans for KCS to move into the aviation sector, and the May 11,1941 KCS public timetable contained no mention of any air connection option. This timetable did include five pages of connections for every rail connecting point between Kansas City and New Orleans/Port Arthur. Rail connections were featured at Kansas City, Pittsburg, Joplin, Neosho, Sallisaw, Fort Smith, Poteau, Howe, DeQueen, Ashdown, Texarkana, Shreveport, Alexandria, New Orleans, Lake Charles and Beaumont. While some rail connections at major stations were always shown, this was a dramatic reversal from the 1940 issues which had promoted airline connections.

The increasing challenges of handling freight and passenger military traffic dictated that all KCS resources be focused on the efficient and safe operation of the railroad for the duration of World War II. With a return to peacetime operation, however, the KCS again sought to enter the airline business. The railroad's May 1939 proposal sought a certificate to operate as a regularly scheduled air carrier, but in June 1946, the railroad incorporated a new subsidiary, Kansas City Southern Skyways. According to KCS president W.N. Deramus, the railroad planned to enter the air transport field as a contract or private carrier. As a contract, non-scheduled carrier of persons or property, KCS Skyways hoped to operate between any points in the United States on an as-needed basis, with operations scheduled to begin about July 10, 1946. At the time, service provided on an irregular basis was outside the scope of the CAB and did not require regulatory approval. The new company was headquartered in Kansas City and initial officers included J.E. Kimmel, vice-president; E.C. Oliver, chief pilot and operations manager, and J.M. Kershaw, superintendent of maintenance. Operations would be available to any airport in the U.S., with charges based on point to point, straight-line mileage, with pick up and delivery service furnished if desired by the shipper. Equipment included three twin-engine Douglas C-47 planes with a payload capacity of 7,000 pounds each, and three single-engine Norseman planes with 1,800 pound payload capacity. [It is uncertain whether the Norseman planes were ever actually purchased.] The C-47s, the Army Air Force version of the civilian DC-3, were capable of speeds from 165 to 180 mph. In late August 1946, KCS Skyways purchased two more C-47 planes and all of the ground equipment of the National Air Express Company, located about 80 miles east of Kansas City in Marshall, MO.

KCS Skyways suffered a crash of one of their C-47s on December 28, 1946, when the loaded cargo plane went down near Walshville, IL (55 miles northeast of St. Louis) killing both the pilot and co-pilot. James Casperson, 25, and Edward C. Oliver, 31, were both from Kansas City, and Oliver was also the chief pilot and operations manager for KCS Skyways. Both men were World War II army air force veterans. The plane was flying from Flint, Michigan to St. Louis, carrying 6,500 pounds of fenders consigned to the Chevrolet General Motors plant at St. Louis. The crash occurred about 8:30 p.m., during a heavy rainstorm. The first report of the crash was received by the Montgomery County sheriff's office from a telegraph operator at Livingston, IL, who had been notified of the crash by the crew of a passing C&EI freight train who had seen the plane go down.

KCS Skyways opened a maintenance base at Coffeyville, KS on February 1, 1947, after leasing space at the former Coffeyville army air field. The base was to be staffed by 8-10 men who would perform routine maintenance and inspections on all of the company's planes. In June 1947, the aviation editor for the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote a feature on KCS Skyways, explaining that the airline was not certified by the CAB to fly scheduled runs and that most runs occurred at night. The idea behind the service was to supply plants during the night with spot production items needed for the next day's operation. The KCS contract with GM began on June 9, flying parts from Detroit to the General Motors plant at Cincinnati, landing after midnight on a nearly daily basis. The company was said to be soliciting loads for the return flights, but so far without much success.

On January 11, 1949, the Civil Aeronautics Board advised Kansas City Southern Skyways that the board had received information suggesting that the airline was operating on other than an irregular basis. KCS Skyways temporarily ceased operations while evaluating legal options, noting that their "irregular" operations occurring five or six days each week were viewed as regular operations by the CAB. Rather than fight the board ruling, KCS elected to discontinue operations effective February 1, 1949, and exit entirely from the aviation transportation business. W.N. Deramus, president of the railroad and the airline, said that since its beginning in May, 1946, the tonnage had not been extensive, although four Douglas DC-3s had been moving freight by private contract between Kansas City, Detroit, St. Louis, Ft. Wayne, New York and Baltimore. "We had built up a good tonnage volume and were handling business for General Motors," Deramus said. "At times we had contracts with Ford, shoe shippers and dress manufacturers. However, its hardly worth trying to buck these restrictions. We have decided to discontinue operations because it looks as if the CAB is not going to let a surface carrier get in the air business." On January 30, 1950, a special meeting of stockholders of Kansas City Southern Skyways was held for the purpose of ratifying an earlier resolution adopted by the Board of Directors to dissolve the corporation. Thus ended the Kansas City Southern's expansion into the aviation industry.